| This text is in a coloured box to separate it from the rest of the chapter. It is a comment about the second part of this working draft chapter, which started as a more or less conventional historical review of the early developments of chemistry in the West. The first parts of the Wikipedia page, History of Chemistry, were used as a template for this early draft. This update interweaves its content with Rudolf Steiner’s Riddles of Philosophy. Also to be used is E.J. Dijksterhuis, The Mechanization of the World Picture. |

Medieval alchemy

See also: Minima naturalia, a medieval Aristotelian concept analogous to atomism

The elemental system used in medieval alchemy was developed primarily by the Persian–Arab alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān and was rooted in the classical elements of Greek tradition.[17] His system consisted of the four Aristotelian elements of air, earth, fire, and water in addition to two philosophical elements: sulphur, characterizing the principle of combustibility, “the stone which burns”; and mercury, characterizing the principle of metallic properties. They were seen by early alchemists as idealized expressions of irreducible components of the universe[18] and are of larger consideration[clarification needed] within philosophical alchemy.

The three metallic principles (sulphur to flammability or combustion, mercury to volatility and stability, and salt to solidity) became the tria prima of the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus. He reasoned that Aristotle’s four-element theory appeared in bodies as three principles. Paracelsus saw these principles as fundamental and justified them by recourse to the description of how wood burns in fire. Mercury included the cohesive principle, so that when it left the wood (in smoke) the wood fell apart. Smoke described the volatility (the mercurial principle), the heat-giving flames described flammability (sulphur), and the remnant ash described solidity (salt).[19]

The philosopher’s stone

Alchemy is defined by the Hermetic quest for the philosopher’s stone, the study of which is steeped in symbolic mysticism, and differs greatly from modern science. Alchemists toiled to make transformations on an esoteric (spiritual) and/or exoteric (practical) level.[20] It was the protoscientific, exoteric aspects of alchemy that contributed heavily to the evolution of chemistry in Greco-Roman Egypt, in the Islamic Golden Age, and then in Europe. Alchemy and chemistry share an interest in the composition and properties of matter, and until the 18th century they were not separate disciplines. The term chymistry has been used to describe the blend of alchemy and chemistry that existed before that time.[21]

The earliest Western alchemists, who lived in the first centuries of the common era, invented chemical apparatus. The bain-marie, or water bath, is named for Mary the Jewess. Her work also gives the first descriptions of the tribikos and kerotakis.[22] Cleopatra the Alchemist described furnaces and has been credited with the invention of the alembic.[23] Later, the experimental framework established by Jabir ibn Hayyan influenced alchemists as the discipline migrated through the Islamic world, then to Europe in the 12th century CE.

During the Renaissance, exoteric alchemy remained popular in the form of Paracelsian iatrochemistry, while spiritual alchemy flourished, realigned to its Platonic, Hermetic, and Gnostic roots. Consequently, the symbolic quest for the philosopher’s stone was not superseded by scientific advances, and was still the domain of respected scientists and doctors until the early 18th century. Early modern alchemists who are renowned for their scientific contributions include Jan Baptist van Helmont, Robert Boyle, and Isaac Newton.

Alchemy in the Islamic world

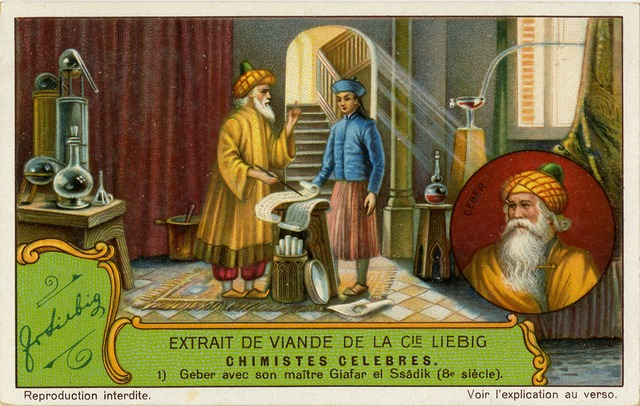

In the Islamic World, the Muslims were translating the works of the ancient Greeks and Egyptians into Arabic and were experimenting with scientific ideas.[24] The development of the modern scientific method was slow and arduous, but an early scientific method for chemistry began emerging among early Muslim chemists, beginning with the 9th-century chemist Jābir ibn Hayyān (known as “Geber” in Europe), who is sometimes regarded as “the father of chemistry”.[25][26][27][28] He introduced a systematic and experimental approach to scientific research based in the laboratory, in contrast to the ancient Greek and Egyptian alchemists whose works were largely allegorical and often unintelligible.[29] He also invented and named the alembic (al-anbiq), chemically analyzed many chemical substances, composed lapidaries, distinguished between alkalis and acids, and manufactured hundreds of drugs.[30] He also refined the theory of five classical elements into the theory of seven alchemical elements after identifying mercury and sulfur as chemical elements.[31][verification needed]

| The sections on alchemy require splitting into two; the early and late periods. Although this a history of the development of chemical ideas in Western Europe, Byzantine, Arabic and Muslim knowledge had an enormous influence on Western thought and knowledge during the later Middle Ages. Therefore those aspects of its history relating to this period will be included here, ready to be carried forward in the following chapter. |

Leave a reply to Ancient Greek Insights – Rethinking the Nature of Substance Cancel reply