The so-called uncuttable atom proved to hold a deeper secret. Something of that story is given in the second half of the Wikipedia article on Atomic Theory:

Discovery of subatomic particles

Main articles: Electron and Plum pudding model

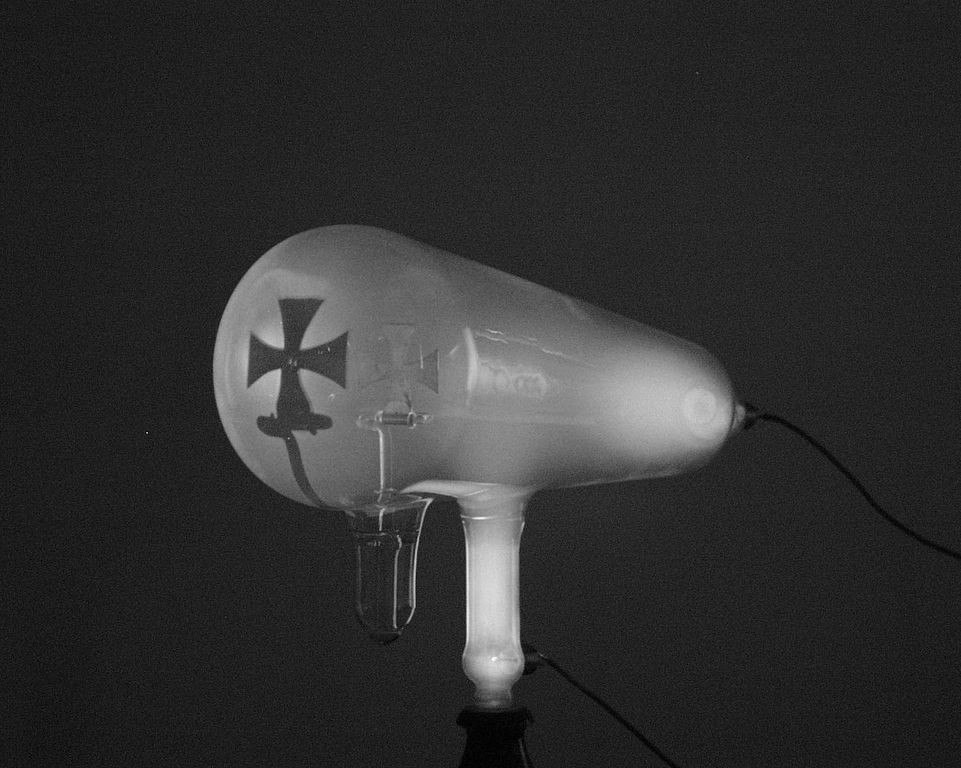

Atoms were thought to be the smallest possible division of matter until 1897 when J.J. Thomson discovered the electron through his work on cathode rays.[18]

A Crookes tube is a sealed glass container in which two electrodes are separated by a vacuum. When a voltage is applied across the electrodes, cathode rays are generated, creating a glowing patch where they strike the glass at the opposite end of the tube. Through experimentation, Thomson discovered that the rays could be deflected by an electric field (in addition to magnetic fields, which was already known). He concluded that these rays, rather than being a form of light, were composed of very light negatively charged particles he called “corpuscles” (they would later be renamed electrons by other scientists). He measured the mass-to-charge ratio and discovered it was 1800 times smaller than that of hydrogen, the smallest atom. These corpuscles were a particle unlike any other previously known.

Thomson suggested that atoms were divisible, and that the corpuscles were their building blocks.[19] To explain the overall neutral charge of the atom, he proposed that the corpuscles were distributed in a uniform sea of positive charge; this was the plum pudding model[20] as the electrons were embedded in the positive charge like raisins in a plum pudding (although in Thomson’s model they were not stationary).

Discovery of the nucleus

Thomson’s plum pudding model was disproved in 1909 by one of his former students, Ernest Rutherford, who discovered that most of the mass and positive charge of an atom is concentrated in a very small fraction of its volume, which he assumed to be at the very centre.

In the Geiger–Marsden experiment, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden (colleagues of Rutherford working at his behest) shot alpha particles at thin sheets of metal and measured their deflection through the use of a fluorescent screen.[21] Given the very small mass of the electrons, the high momentum of the alpha particles, and the low concentration of the positive charge of the plum pudding model, the experimenters expected all the alpha particles to pass through the metal foil without significant deflection. To their astonishment, a small fraction of the alpha particles experienced heavy deflection. Rutherford concluded that the positive charge of the atom must be concentrated in a very tiny volume to produce an electric field sufficiently intense to deflect the alpha particles so strongly.

This led Rutherford to propose a planetary model in which a cloud of electrons surrounded a small, compact nucleus of positive charge. Only such a concentration of charge could produce the electric field strong enough to cause the heavy deflection.[22]

First steps toward a quantum physical model of the atom

Main article: Bohr model

The planetary model of the atom had two significant shortcomings. The first is that, unlike planets orbiting a sun, electrons are charged particles. An accelerating electric charge is known to emit electromagnetic waves according to the Larmor formula in classical electromagnetism. An orbiting charge should steadily lose energy and spiral toward the nucleus, colliding with it in a small fraction of a second. The second problem was that the planetary model could not explain the highly peaked emission and absorption spectra of atoms that were observed.

Quantum theory revolutionized physics at the beginning of the 20th century, when Max Planck and Albert Einstein postulated that light energy is emitted or absorbed in discrete amounts known as quanta (singular, quantum). In 1913, Niels Bohr incorporated this idea into his Bohr model of the atom, in which an electron could only orbit the nucleus in particular circular orbits with fixed angular momentum and energy, its distance from the nucleus (i.e., their radii) being proportional to its energy.[23] Under this model an electron could not spiral into the nucleus because it could not lose energy in a continuous manner; instead, it could only make instantaneous “quantum leaps” between the fixed energy levels.[23] When this occurred, light was emitted or absorbed at a frequency proportional to the change in energy (hence the absorption and emission of light in discrete spectra).[23]

Bohr’s model was not perfect. It could only predict the spectral lines of hydrogen; it couldn’t predict those of multi-electron atoms. Worse still, as spectrographic technology improved, additional spectral lines in hydrogen were observed which Bohr’s model couldn’t explain. In 1916, Arnold Sommerfeld added elliptical orbits to the Bohr model to explain the extra emission lines, but this made the model very difficult to use, and it still couldn’t explain more complex atoms.

Discovery of isotopes

Main article: Isotope

While experimenting with the products of radioactive decay, in 1913 radiochemist Frederick Soddy discovered that there appeared to be more than one element at each position on the periodic table.[24] The term isotope was coined by Margaret Todd as a suitable name for these elements.

That same year, J.J. Thomson conducted an experiment in which he channelled a stream of neon ions through magnetic and electric fields, striking a photographic plate at the other end. He observed two glowing patches on the plate, which suggested two different deflection trajectories. Thomson concluded this was because some of the neon ions had a different mass.[25] The nature of this differing mass would later be explained by the discovery of neutrons in 1932.

Discovery of nuclear particles

Main articles: Atomic nucleus and Discovery of the neutron

In 1917 Rutherford bombarded nitrogen gas with alpha particles and observed hydrogen nuclei being emitted from the gas (Rutherford recognised these, because he had previously obtained them bombarding hydrogen with alpha particles, and observing hydrogen nuclei in the products). Rutherford concluded that the hydrogen nuclei emerged from the nuclei of the nitrogen atoms themselves (in effect, he had split a nitrogen).[26]

From his own work and the work of his students Bohr and Henry Moseley, Rutherford knew that the positive charge of any atom could always be equated to that of an integer number of hydrogen nuclei. This, coupled with the atomic mass of many elements being roughly equivalent to an integer number of hydrogen atoms – then assumed to be the lightest particles – led him to conclude that hydrogen nuclei were singular particles and a basic constituent of all atomic nuclei. He named such particles protons. Further experimentation by Rutherford found that the nuclear mass of most atoms exceeded that of the protons it possessed; he speculated that this surplus mass was composed of previously-unknown neutrally charged particles, which were tentatively dubbed “neutrons“.

In 1928, Walter Bothe observed that beryllium emitted a highly penetrating, electrically neutral radiation when bombarded with alpha particles. It was later discovered that this radiation could knock hydrogen atoms out of paraffin wax. Initially it was thought to be high-energy gamma radiation, since gamma radiation had a similar effect on electrons in metals, but James Chadwick found that the ionization effect was too strong for it to be due to electromagnetic radiation, so long as energy and momentum were conserved in the interaction. In 1932, Chadwick exposed various elements, such as hydrogen and nitrogen, to the mysterious “beryllium radiation”, and by measuring the energies of the recoiling charged particles, he deduced that the radiation was actually composed of electrically neutral particles which could not be massless like the gamma ray, but instead were required to have a mass similar to that of a proton. Chadwick now claimed these particles as Rutherford’s neutrons.[27] For his discovery of the neutron, Chadwick received the Nobel Prize in 1935.

Quantum physical models of the atom

Main article: Atomic orbital

In 1924, Louis de Broglie proposed that all moving particles — particularly subatomic particles such as electrons — exhibit a degree of wave-like behaviour. Erwin Schrödinger, fascinated by this idea, explored whether or not the movement of an electron in an atom could be better explained as a wave rather than as a particle. Schrödinger’s equation, published in 1926,[28] describes an electron as a wavefunction instead of as a point particle. This approach elegantly predicted many of the spectral phenomena that Bohr’s model failed to explain. Although this concept was mathematically convenient, it was difficult to visualise, and faced opposition.[29] One of its critics, Max Born, proposed instead that Schrödinger’s wavefunction described not the electron but rather all its possible states, and thus could be used to calculate the probability of finding an electron at any given location around the nucleus.[30] This reconciled the two opposing theories of particle versus wave electrons and the idea of wave–particle duality was introduced. This theory stated that the electron may exhibit the properties of both a wave and a particle. For example, it can be refracted like a wave, and has mass like a particle.[31]

A consequence of describing electrons as waveforms is that it is mathematically impossible to simultaneously derive the position and momentum of an electron. This became known as the Heisenberg uncertainty principle after the theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg, who first described it and published it in 1927.[32] This invalidated Bohr’s model, with its neat, clearly defined circular orbits. The modern model of the atom describes the positions of electrons in an atom in terms of probabilities. An electron can potentially be found at any distance from the nucleus, but, depending on its energy level, exists more frequently in certain regions around the nucleus than others; this pattern is referred to as its atomic orbital. The orbitals come in a variety of shapes – sphere, dumbbell, torus, etc. – with the nucleus in the middle.[33]

In parallel with this research into the nature of the mysterious atom, scientists were discovering that chemical elements can indeed transmute from one into another – either naturally by radioactivity – or artificially, though under exceptional circumstances. I give below part of the Wikipedia article on this transmutation research:

Alchemy

The term transmutation dates back to alchemy. Alchemists pursued the philosopher’s stone, capable of chrysopoeia – the transformation of base metals into gold.[3] While alchemists often understood chrysopoeia as a metaphor for a mystical, or religious process, some practitioners adopted a literal interpretation, and tried to make gold through physical experiment. The impossibility of the metallic transmutation had been debated amongst alchemists, philosophers and scientists since the Middle Ages. Pseudo-alchemical transmutation was outlawed[4] and publicly mocked beginning in the fourteenth century. Alchemists like Michael Maier and Heinrich Khunrath wrote tracts exposing fraudulent claims of gold making. By the 1720s, there were no longer any respectable figures pursuing the physical transmutation of substances into gold.[5] Antoine Lavoisier, in the 18th century, replaced the alchemical theory of elements with the modern theory of chemical elements, and John Dalton further developed the notion of atoms (from the alchemical theory of corpuscles) to explain various chemical processes. The disintegration of atoms is a distinct process involving much greater energies than could be achieved by alchemists.

Modern physics

It was first consciously applied to modern physics by Frederick Soddy when he, along with Ernest Rutherford, discovered that radioactive thorium was converting itself into radium in 1901. At the moment of realisation, Soddy later recalled, he shouted out: “Rutherford, this is transmutation!” Rutherford snapped back, “For Christ’s sake, Soddy, don’t call it transmutation. They’ll have our heads off as alchemists.”[6]

Rutherford and Soddy were observing natural transmutation as a part of radioactive decay of the alpha decay type. The first artificial transmutation was accomplished in 1925 by Patrick Blackett, a research fellow working under Rutherford, with the transmutation of nitrogen into oxygen, using alpha particles directed at nitrogen 14N + α → 17O + p. [7] Rutherford had shown in 1919 that a proton (he called it a hydrogen atom) was emitted from alpha bombardment experiments but he had no information about the residual nucleus. Blackett’s 1921-1924 experiments provided the first experimental evidence of an artificial nuclear transmutation reaction. Blackett correctly identified the underlying integration process and the identity of the residual nucleus. In 1932, a fully artificial nuclear reaction and nuclear transmutation was achieved by Rutherford’s colleagues John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton, who used artificially accelerated protons against lithium-7 to split the nucleus into two alpha particles. The feat was popularly known as “splitting the atom,” although it was not the modern nuclear fission reaction discovered in 1938 by Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner and their assistant Fritz Strassmann in heavy elements.[8]

In 1924, in the fifth of Rudolf Steiner’s Agriculture lectures, he spoke of a hidden alchemy in organic processes. He preceded this with a paragraph which has haunted me for some time now:

There is something you must know in this connection. For the scientists of to-day, they will no longer argue that there is such entire confusion on our part as they would have done a short time ago. Are not they themselves already speaking frankly of a transmutation of the elements? Observation of several elements has tamed the materialistic lion in this respect, if I may say so. Processes, however, that are taking place around us all the time are as yet utterly unknown. If they were known, people would more readily believe such things as I have just explained.

It has taken me some time to begin to learn something about the probable alchemical source of this reference. Rather embarrassingly it was in The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Alchemy: The Magic and Mystery of the Ancient Craft Revealed for Today by Dennis William Hauck, that I found the clearest explanation, in a section headed The Lions of Alchemy.

Lions are important symbols… Chemically the lion is any… fixed substance obtained from the metals…

Philosophically, the Green Lion is the raw forces of nature or the subconscious that we are seeking to tame, and the Red Lion is the assimilation or control of those forces. In the final stages of the work, the Red Lion grows wings. The Winged Lion is the volatile or spiritual aspect of a substance, which is the sublimated salt used to make the Philosopher’s Stone.

Therefore, in all probability, Steiner’s reference to the taming of the material lion refers to the material aspects of alchemy – the transmutation of chemical elements – such as was observed by Rutherford and Soddy.

Leave a reply to Table of Contents – Rethinking the Nature of Substance Cancel reply