| This website is under reconstruction! Please be patient. The book is in the process of being researched, reviewed and written. – The Table of Contents – The Home page – links via either the image or the title at the top of the page – contain all my current and previous drafts, thoughts and notes. |

This book was inspired by three little known paragraphs in the fifth of Rudolf Steiner’s Biodynamic Agriculture lectures, in which he introduced the possibility of alchemy in living organisms.1 It is the aim of this book to enable something of an understanding of what Steiner said here. It will be a challenging journey, for this subject is one of the greatest mysteries known to science — the nature of substance and the so-called atom. As your guide it is my wish to make our journey as smooth as I can, by taming the treacherous waters wherever possible, but not by avoiding them — as many have done before.

No previous knowledge has been assumed. For those who do have prior knowledge, or come to this book with preconceptions; this may in fact be a disadvantage. It took me many years to unlearn much that I had previously considered to be true—both in mainstream science and philosophy. I have taken the teachings of Rudolf Steiner and others as guidance or indications, not as gospel truths. It is my hope that this book will also serve as guidance, or even inspiration; either as inspiration for future research, or as a guide to help us better appreciate something of the awe and wonder we may experience of the world around us and of which we are very much a part. It has also been written as an appreciation of the many scientists and philosophers, poets and theologians, past and present, whose work enabled this book to be written.

Indications for a Hidden Alchemy in Living Processes – Biodynamics

From the fifth of Rudolf Steiner’s Biodynamic Agriculture lectures:

There is something you must know in this connection. For the scientists of to-day, they will no longer argue that there is such entire confusion on our part as they would have done a short time ago. Are not they themselves already speaking frankly of a transmutation of the elements? Observation of several elements has tamed the materialistic lion in this respect, if I may say so.2 Processes, however, that are taking place around us all the time are as yet utterly unknown. If they were known, people would more readily believe such things as I have just explained.

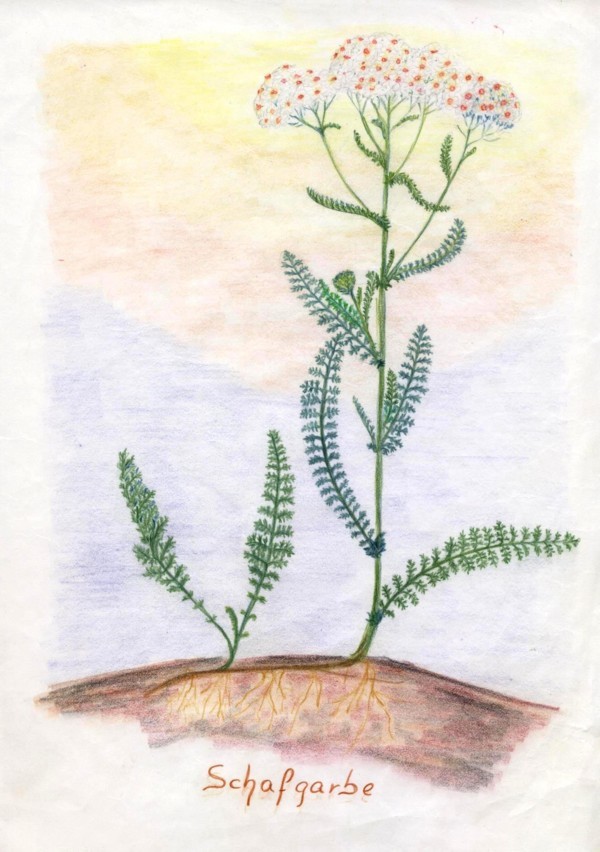

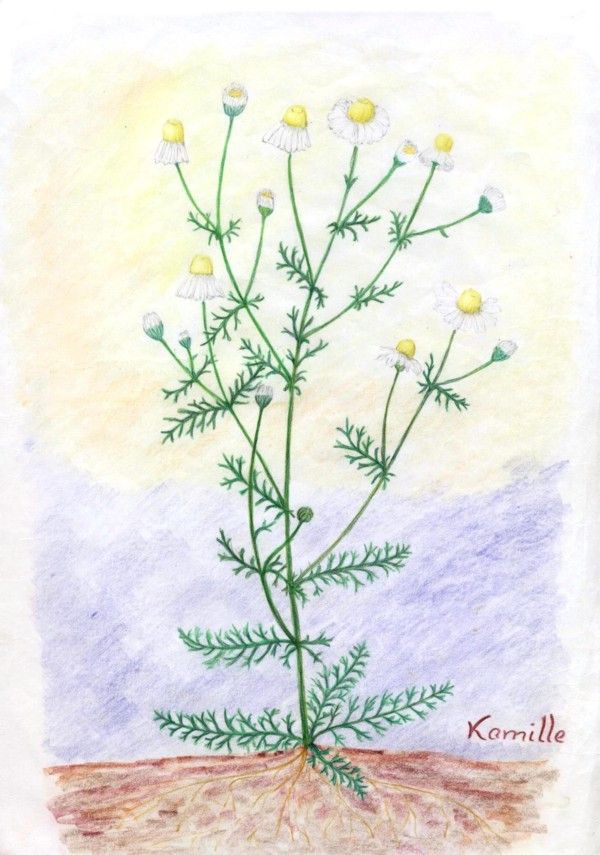

I know quite well, those who have studied academic agriculture from the modern point of view will say: “You have still not told us how to improve the nitrogen-content of the manure.” On the contrary, I have been speaking of it all the time, namely, in speaking of yarrow, camomile and stinging nettle. For there is a hidden alchemy in the organic process. This hidden alchemy really transmutes the potash, for example, into nitrogen, provided only that the potash is working properly in the organic process. Nay more, it even transforms into nitrogen the limestone, the chalky nature, if it is working rightly.

Even externally, in a quantitative chemical analysis as it were, the relationship… might well be revealed. The fact is that under the influence of hydrogen, limestone and potash are constantly being transmuted into something very like nitrogen, and at length into actual nitrogen. And the nitrogen which is formed in this way is of the greatest benefit to plant-growth. We must enable it to be thus engendered by methods such as I have here described.3

Rudolf Steiner, 5th Agriculture Lecture, Koberwitz, 1924.

The Taming of the Atom: A Sub-Natural Phenomenon

Georg Unger, in his lectures ‘On Nuclear Energy and the Occult Atom’ (Von Wesen der Kernenergie), wrote of Rudolf Steiner having written and lectured on three aspects of the atom:

- The hypothetical atom of the 19th century;4

- The atom as a sub-sensible entity, responsible for many of the strange phenomena studied by chemists and physicists from the early 20th century.5

- An “occult atom” as a spiritual entity.6

When Steiner said that ‘observation of several elements has tamed the materialistic lion’, it was with respect to the atom’s second aspect. Presumably he was referring to the work of scientists such as William Crookes, Marie Curie and Ernest Rutherford.7

Once the theoretical and practical work by Albert Einstein, in 1905, had been confirmed experimentally by Jean Baptiste Perrin just three years later, even the ‘old fighter against atomistics’, Wilhelm Ostwald, was converted to the idea of their existence as a real phenomenon of (sub-)nature.8

The earliest mainstream proof of atoms being capable of transmutation was made by Soddy and Rutherford, who discovered that radioactive thorium was converted into radium and alpha ‘particle’ radiation in 1901. By 1907 alpha ‘particles’ were shown to be helium nuclei.9

Biological Transmutation of Chemical Elements

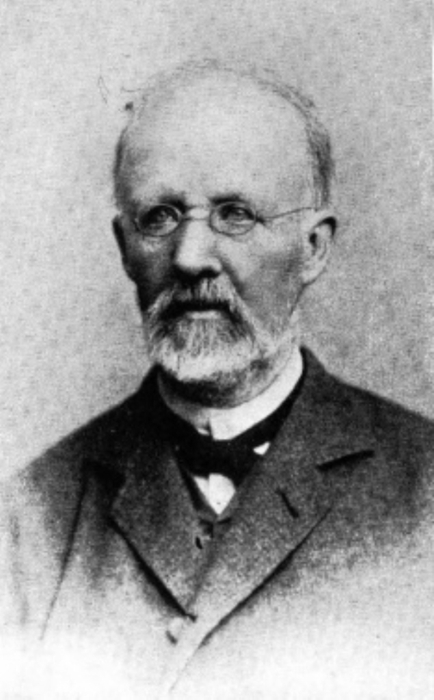

From the 1840s most scientists believed that chemical elements were characterised by the properties and actions of invisible, immutable atoms. The possibility of living organisms being able to transmute the chemical elements of which they were composed was considered heresy. The biological transmutation experiments of Albrecht Herzeele from 1873 to 1883 were considered deluded, and the phenomenon is still considered impossible by most scientists.

Fortunately Herzeele’s work was described by the philosopher W. H. Preuss. Though there is no evidence that Steiner knew of Herzeele, he certainly knew about Preuss; Steiner wrote about Preuss in his ‘Riddles of Philosophy’. Herzeele’s work was rediscovered by Rudolf Hauschka and published in the German edition of his book Substanzlehre (1942).10

Shortly after Steiner’s Agriculture lectures, given in 1924, further inorganic and biological transmutation research was conducted. This included the work of Amé Pictet (1925), P. Freundler (1928), Earle Augustus Spessard (1940), Henri Spindler (1959), Pierre Baranger (1950-70), Correntin Louis Kervran (1960-80), and others,11 including Holleman (1975-89), and Jean-Paul Biberian.12 The most convincing modern research into the biological transmutation of chemical isotopes (elements) was conducted by Vladimir Vysotskii and Alla Kornilova from the 1990s.13 Despite this research the phenomenon is still considered impossible by mainstream science, for it breaks a number of theoretical dogmas.

The central theme of this book is a rethinking of the mainstream, academic conception of the nature of substance. It is therefore concerned with a transformation in our understanding—a spiritual or alchemical journey. The book is divided into three parts, each composed of seven chapters.

Part I concerns itself with the ideas necessary for an understanding of that which is to be transformed—namely mainstream (Western) philosophical and scientific conceptions of substance, as developed through history.

Part II concerns the reason for this book—that in order for the biological transmutation phenomenon to be understood, we require a transformation (paradigm shift) in our understanding of the nature of substance.

Part III concerns the final and most challenging stage of our journey—the transformation itself. This involves an attempt to apply the spiritual scientific indications of Rudolf Steiner to the development of a rethinking of the nature of substance, matter and the so-called atom. Of note is that in this book I consider the word spirit to mean any non-material idea or process. In this I may differ from its use by others who may limit it’s use to transcendental, super- (beyond) natural phenomena.

Part I: Genesis – On Generation and Corruption

Our story in the first part of this book seeks for revelation in creation in relation to two different scientific worldviews whose development started during the time of the Ancient Greek philosophers. My title was inspired by Aristotle’s definition of holistic change, genesis, which is normally translated as coming to be, generation, or as the Bible, creation. We will discover that both Plato and Aristotle believed that reality consisted of a unity of;

- Physical matter, perceived by our physical senses, and

- Ideal form, conceived by our mind –

- They were realists – they believed that both matter and ideal forms exist independently of human beings.

It was out of this worldview that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Rudolf Steiner developed their ideas.

We also learn how an alternative, atomic or corpuscular view, which was most famously taught by Democritus, was hated so much by Plato that he wished all of his burned! It was from this worldview that modern academic science developed.

Chapter 1 starts our journey with a consideration of some of the earliest beginnings of a holistic worldview. We will see how, contrary to popular accounts, philosophers such as Parmenides, Heraclitus and Plato saw the world as presented to us in two different ways.

- There is the way of aletheia, the way of truth. This involves the sense free perception of eternal, ideal, unchanging, universal, archetypal forms – an account of which was called logos. Because they are eternally unchanging, they are independent of time. Such eternal truths have an existence independent of us. Seen by the mind, we know them as concepts. When we understand something we say “I see” even if we have our eyes closed!

- And there is the way of doxa, the way of opinion. Material stuff, that which is perceived by our physical senses, is measurable stuff. Because our physical measurements are never perfectly accurate we can only hold personal opinions about them. Physical matter is also subject to the ever changing passage of time – continuously decaying and coming to be. Our personal ‘mental pictures’ of physical objects, gained by way of our physical senses, are called percepts.

- This dual, twofold appearance of reality as experienced by us human beings is rarely understood today. The modern philosophies of phenomenology and hermeneutics are the closest academic to developing this holistic worldview; one of material parts (percepts) and ideal wholes (concepts). My main guide has been Henri Bortoft, who helped me understand the teachings of Aristotle, Gadamer, Goethe, Heidegger, Heraclitus, Parmenides, Plato and Steiner.

Plato’s students were expected to work hard to develop the ability to think for themselves. His dialogues were therefore deliberately designed to confuse his audience. Fortunately for us, some modern philosophers such as Mary Louise Gill, Catherine Osborne/ Rowett and Joe Sachs have helped me gain a basic understanding. By way of an introduction, Plato’s cave analogy is the easiest to understand.

Chapter 2 guides us through some of the teachings of Aristotle. Henri Bortoft, Mary Louise Gill, Joe Sachs, Rudolf Steiner and Jakob Ziguras have all shown me how he agreed with and further developed the holistic worldview of Plato. The unity of physical matter and idea form, Aristotle called hylomorphism. He explained in a number of his books how one classical element might transform into another. Key to his understanding is the word ousia, which many people have translated as substance, one of the central themes of this book (of which more in the following chapter). Also of importance to our spiritual journey is how we acquire such knowledge. The equivalence of Aristotle’s word arche (or archai) is explored in relation to the Urphänomene (archetypal form) of Goethe (of which more in Part III).

In Chapter 3 I move out of my comfort zone and, with the help of Rudolf Steiner, show how after Aristotle Western philosophy moved away from its former interest in natural philosophy and became more interested in human actions. In German such studies are called Geisteswissenschaften, a translation of the nineteenth century English concept of moral philosophy, and which followers of the German speaking Rudolf Steiner have translated back into English as spiritual science. Of particular interest to us here is how the original Ancient Greek word ousia, referring to the ideal archetypal forms, or spiritual essences of all physical things that exist, became demoted by the early Christian theologist Saint Augustine of Hippo.

My initial understanding, based on Joe Sachs commentary to his translation of Aristotle’s Metaphysics, is that the Roman Christian church wished to separate earthly from heavenly entities. The concept spiritual was reserved for heavenly matters. Therefore ousia was translated via Latin into English as substance – that which stands underneath. My initial reaction on discovering this was sadness. Even when I was a devout atheist, I always felt that the qualities of everyday things and their associated non-material processes were something special, even magical in some unfathomable sense.

Plato’s cave analogy describes a prisoner who escapes from being tied up in the dark, who had previously only been able to see flat shadows of hidden forms projected onto the wall in front of him. They escape into a light illuminated world possessing an extra dimension of ideal spiritual forms. I would be delighted if I managed to share some of that joy with the readers of this book.

At least on my initial reading, this was what Roman Christianity seemed to want to replace. Nevertheless, the principles of Christian morality – as taught in the New Testament – are something shared by most of us human. Love, compassion for others, awareness of the consequences of our deeds are principles of the highest order. Personally, I believe that they are essential to the development of a scientific worldview. Nevertheless, regarding the existence of higher beings, though touched on in chapters 5 and 16, I am now open to such possibilities, though they leave me somewhat confused. Fortunately such esoteric, theological considerations are beyond the scope of this particular book.

Chapter 4 returns us to Classical Greece and the atomic or corpuscular theory of matter. Plato, based on the ideas of both Parmenides and Heraclitus, attempted to marry sense and reason. Aristotle developed these ideas further to explain change as a coming-to-be. The philosopher Democritus envisaged merely the changes of the positions in empty space (void) of four types of hypothetical indestructible, uncuttable atoms to explain all qualities, quantities and change. “By convention (nomos) sweet is sweet, bitter is bitter, hot is hot, cold is cold, colour is colour; but in truth there are only atoms and the void.” But where is the human being in this picture? There can be a physical brain, but where is the spiritual mind, the soul, or the will? Where is poetry, morality or love? Ironically, his ideas were most famously encapsulated in an epic poem, De Rerum Naturae, by the Roman epicurean philosopher Lucretius. Further challenges to the realist view (that universal ideas exist independently of those who conceive them) arose during Medieval times with Christian scholars. This was nominalism. This concept is that universal ideas are the creations of our own minds, communicated between us using empty words. In chapter 6 we will see how such ideas influenced Renaissance thinkers such as Descartes.

In Chapter 5 we will see how influential the study of alchemy has been, especially in the fields of chemistry and medicine. Paracelsus was one of the most famous. Such ideas were highly influential right through the Renaissance period till the very early nineteenth century. Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe are particular examples. It is important to note that true alchemy was never about the search for physical gold but for development of the spiritual quality of gold in the alchemists themselves. Needless to say many greedy individuals attempted (and failed) to become rich regardless of those who taught them otherwise.

In Chapter 6 we see how the simplifying our notion of reality, during the Renaissance, mathematical physics was able to make tremendous advances. Galileo, Descartes and Newton were amongst the most successful. However, when Galileo formally separated what he considered to be the subjective mind from from the objective world outside, it had several consequences. Human beings became detached observers. The physical universe, including ourselves, became seen as a mechanical clockwork machine. God was seen as a divine clock-maker. In a purely mechanical universe, everything would be pre-determined and free will, impossible. Nevertheless, Newton believed that it was God who designed the universe and continued to make necessary adjustments.

In Chapter 7 we see how the study of chemistry also made big advancements because of the scientific revolution of the Renaissance. The new experimental impetus promoted by Francis Bacon and Galileo, combined with both mathematics and the atomic or corpuscular theories promoted by all of the physicists in the previous chapter, created what has been called the chemical revolution. Jan Baptist van Helmont, Robert Boyle and Antoine Lavoisier all played their part. And the culmination of their work was the law of the conservation of matter. In 1787 Lavoisier expressed it thus: “We may lay it down as an incontestable axiom, that, in all the operations of art and nature, nothing is created; an equal quantity of matter exists both before and after the experiment; the quality and quantity of the elements remain precisely the same; and nothing takes place beyond changes and modifications in the combination of these elements. Upon this principle the whole art of performing chemical experiments depends: We must always suppose an exact equality between the elements of the body examined and those of the products of its analysis.”14

However, we will learn that whilst chemical substances and their reactions have physical properties – they may change colour, cause explosions or emit obnoxious smells – their underlying causes are not the same as the mechanical behaviour of solid objects. We can open the back of a mechanical clock and the clockwork mechanism can be directly perceived. However, the underlying causes of chemical reactions are – by definition – occult phenomena, for the supposed causal entities – hypothetical (at that time) atoms or corpuscles – are invisible to our physical senses.

Part II: Crossing the Threshold – Atom, Isotope and Transmutation

We now arrive at the pivotal centre of this book, which effectively starts in the nineteenth century. The invisible atom becomes central to almost all scientific endeavour. Whilst science became involved in the study of what Rudolf Steiner called sub-nature, during this same century there was also a revived interest in the super-natural. Of particular interest to us is that by the beginning of the twentieth century Rudolf Steiner was able to say that “the scientists of to-day, they will no longer argue that there is such entire confusion on our part as they would have done a short time ago. Are not they themselves already speaking frankly of a transmutation of the elements? Observation of several elements has tamed the materialistic lion in this respect, if I may say so.”15

In Chapter 8 we learn how, during the course of the nineteenth century, despite an increasing belief in this invisible entity, evidence for the invisible atom remained hypothetical, and many were sceptical. A surprising number of chemists still believed in vitalism. Experiments by Wohler in 1828 and Wiegmann and Polstorff in 1842 were seen as definitive proof that living organisms were subject to exactly the same laws of chemistry and physics as dead, inorganic nature.16 By 1908 most of the atom’s former sceptics, including the German chemist Ostwald, eventually accepted the existence of the atom after the Nobel Prize winning work of Einstein (predictive theory) and Perrin (experimental proof). We might assume this was the end of Plato and Aristotle’s holistic worldview, or of alchemy. One might think that we should merely accept the idea of a universe of atoms and void. However, it is said that the night is darkest before the dawn. Rudolf Steiner has said [WHERE??!!] that it was essential for the old ways of thinking to die out before they can be replaced by something new.

In Chapter 9 we will see how both Baron von Herzeele and the philosopher Wilhelm Heinrich Preuss disagreed very much with the prevailing atomic world view. Their ideas were largely shaped by the late eighteenth, early nineteenth century German literary artist, philosopher and scientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who effectively founded a phenomenological approach to the study of nature.17 Between 1876 and 1883 Herzeele conducted a series of very careful experiments involving the chemical analysis of germinating seeds. His published results supported the idea that plants are capable of transmuting one chemical element into another. This is forbidden by Lavoisier’s law: “nothing takes place other than changes and modifications in the combinations of the elements“.

Meanwhile, Rudolf Hauschka had been inspired by Rudolf Steiner and the philosopher Preuss to trace possibly the only surviving copy of Baron von Herzeele’s research. Many scientists came to be aware of this little understood phenomenon, directly or indirectly, via Hauschka’s rediscovery. Their motivation was an interest in the exceptional properties of life.

In chapter 10 we see how during the course of the next few decades, by way of Marie Curie, Ernst Rutherford and others (as detailed in Chapter 13), Lavoisier’s Law was seen to be broken for dead inorganic matter as well. Experiments with natural radioactivity and artificial atom smashing studies brought the subject of alchemy back into the popular press. Therefore, in 1926 when the Swiss chemist Amé Pictet found high amounts of the noble gas argon in fermenting yeast he speculated that this may be due to radioactive decay of potassium, possibly brought about “under the influence of life“. Unlike Herzeele and Hauschka his motivation came from the new field of nuclear chemistry. Nevertheless, his work was ignored. Chemical element transmutations were the exclusive realm of nuclear physics laboratories. For a chemist to propose such a phenomenon in living organisms was tantamount to vitalism and alchemy and therefore impossible. Definitive proof for the radioactive decay of potassium-40 into argon-40 was only obtained in 1948.18 The fisheries chemist Freundler also made observations relating to tin and iodine in seaweed, whose atomic numbers were similar enough for a transmutation to be considered possible.

Following on the journey from Herzeele to Preuss, to Steiner, to Hauschka, to Baranger and thence to the Frenchman Corentin Louis Kervran in the 1960s. His main contribution was the promotion of the phenomenon via popular books and magazines. He claimed that his simplistic mechanism was able to account for the observations which were otherwise considered impossible by mainstream science.19 Unfortunately both Kervran’s experimental methods and his theoretical mechanism have received severe criticism, not only by mainstream science, but also by some of those who very much believe in the phenomenon. This includes Vladimir Vysotskii, a nuclear physicist from the Ukraine. His biological transmutation experiments have provided the strongest evidence I have seen. Another scientist who was sceptical of the quality of Kervran’s research was Wim Holleman, whose transmutation studies inspired the writing of this book.

Chapter 11 focuses on the scientist whose biological transmutation research inspired the writing of this book; Wim Holleman. As a chemist he had been particularly inspired by Steiner’s fifth Agriculture lecture (as quoted above). His experimental results with the green alga, Chlorella, were unexpected. Sadly they have not yet been repeated.20

Even more intriguing were the results of Jean-Paul Biberian. His Marinobacter experiment was conducted with the hope of a replication of Holleman’s successful experiment. Biberian’s experimental details are also given in this chapter. Nevertheless, his experiments were only of a preliminary nature and have not yet been repeated.

In Chapter 12 the superb biological transmutation research of the Ukrainian Vladimir Vysotskii is looked at in detail. His results are to my mind are the only entirely convincing ones so far published.

He is also involved with the so-called phenomenon of cold fusion. This phenomenon of low energy nuclear transmutations involving deuterium (heavy hydrogen) and platinum, though much better studied than biological transmutations, is also disbelieved by the majority of mainstream scientists! Nevertheless, Vysotskii’s knowledge of quantum mechanics has enabled him to propose that it is the dynamic nature of the biological environment that enables micro-organisms, and by extension, plants and animals to achieve what is supposed to be impossible.

Of importance to this book is his proof that it is chemical isotopes that are the fundamental entities in such transmutations. These are different forms of chemical element which more or less only vary in their properties with regard their weight. The story of how they were discovered is covered in the following Chapter.

In Chapter 13 we follow physics across the threshold and explore early investigations of spooky non-mechanical action-at-a-distance phenomena such as gravity, electricity and magnetism. During second half of the nineteenth century several physicists had an interest in paranormal phenomena and believed that the radiant electrical phenomena were physical manifestations from such mysterious realms. Though their investigations failed to connect them with the spirits of departed souls, their discoveries were certainly mysterious.

The practical experiments of Faraday and the mathematical models of James-Clerk Maxwell indicated that light and related phenomena were manifestations of electro-magnetic waves which were believed to travel through a hypothetical ether. Meanwhile related researches by Henri Becquerel and Marie Curie led to the discovery of radioactivity. This demonstrated that atoms were not indestructible. The atom-smashing experiments of Rutherford and Soddy resulted in new conceptions for the structure of the atom. Natural radioactive or laboratory induced decay of chemical elements was found to create substance with the same chemical properties but differing atomic weights. These were called isotopes, and became the new fundamental entity of nuclear physics and chemistry – as was referred to in the previous chapter.

In Chapter 14 we see how the mechanical model of thermodynamics lead to unexpected results relating to the light emissions of heated objects. Max Planck could only describe this phenomenon by means of a series of discrete energy emissions which he named quanta (plural of quantum). Such behaviour was unexplainable by means of any earlier classical (material) physics. However the mathematics he used to model this strange phenomenon was taken directly from mechanical models of invisible particles. This new branch of physics therefore became known as quantum mechanics. This was despite their having discovered that this was a strange, hidden, occult, sub-natural realm that bore little or no relation to the physical realm for which such mathematical forms were originally intended. The imagery associated with the mathematics was therefore merely a convenient fiction and any understanding was only nominalist rather than realist in nature.

Part III: Sublimation – Rudolf Steiner, Life and the Possibility of a Goethean Physics

This concluding part explores some of the limits of current understanding within the worldviews of Goethe and Steiner. Many Anthroposophists have written about their understandings of material, etheric, astral and ego realms which may have a bearing on the growth of plants, animals and ourselves. Their conceptions have sometimes appeared contradictory. The emphasis here is on the mathematical indications given by Rudolf Steiner regarding the etheric realm. However, the etheric is just one of several influences on the inorganic and organic realms – these too need to be explored.

In chapter 15 Goethe’s holistic worldview is considered as the foundation of Rudolf Stenier’s conceptions. Both Herzeele and Holleman were also strongly influenced by his ideas as a way to further scientific progress.

Wim Holleman recommended that the phenomenon might best be investigated by way of a Goethean scientific methodology. The third part of this book starts with Chapter 15’s exploration of the scientific work and ideas of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe—German poet, philosopher, and ‘observer of nature’. His realist belief — no matter without spirit (Universal, Ideal Form), no spirit without matter — is Aristotelian.21 His methodology, and the insights derived therefrom, are explored in some detail, for it forms the foundation for the rest of this book.

Chapter 16 details how Goethe’s worldview formed the philosophical basis of Rudolf Steiner’s early natural philosophical publications. Steiner later gave indications for a new natural scientific worldview based, not only on Goethean scientific foundations, but also alchemy, Ancient Greek philosophy, recent developments in projective geometry, and his own spiritual insights.In particular was his concept of the four ethers, of greatest importance to this work, and as far as I can ascertain, Steiner was the first to conceive of such cosmic forces, at least in this way. This chapter describes his indications for the nature of the atom in terms of this etheric realm. It also introduces some of his wider theosophical insights relating to the fourfold-nature of the human being and the associated cosmic forces. Like Plato before him, he also indicated the importance of mathematics and the geometry of the different spatial realms in the further development of spiritual science.22

In Chapter 17 it is shown how Steiner’s projective geometry indications were taken up by several scientists, including the chemist and mathematician George Adams (Kauffman).23

Chapter 18 sits right in the middle of this last part of the book. Olive Whicher started as George Adams assistant, and thanks to her wonderful farsighted artistic and mathematical talents she was able lift Adams’ research to a higher level. Works such as The Plant Between Sun and Earth and Projective Geometry – Creative Polarities in Space and Time are my inspiration here. However, her work largely focussed on the etheric realm. However, after reading Glen Atkinson’s The Problem of the Etheric Formative Forces, I feel it is important to place here some of the many ideas different Anthroposophists have regarding the four ethers and formative forces in general. Jochen Bochenmuhl, Karl Koenig, Ernst Lehrs, Bernard Lievegoed, Ernst Marti, Hermann Poppelbaum, Paul Schiller, many references by Rudolf Steiner, Gunther Wachsmuth, Ita Wegman, are those I am mainly aware of who have made contributions, though I am sure there are others. My challenge is that many of their ideas are seemingly contradictory. Just what principles do they all hold in common? What can we learn from them?

It is in Chapter 19 that we learn how Nick Thomas’ insight (and hard work!) enables our goal to be achieved (or, at the very least, the possibilities of doing so). By following the indications of Rudolf Steiner, Thomas was able to independently derive the Schrödinger wave equation. I cannot emphasise enough how truly significant this result is. Schrödinger’s wave equation (and its mathematical equivalents) forms the basis of the mainstream understanding of atomic and sub-atomic phenomena. Mainstream science developed quantum mechanics to describe the behaviour of such sub-natural entities. As is explained in Chapter 7, it is based on entirely mechanical, mathematical models which avoid all attempts at meaningful understanding. It is just possible that Nick Thomas’ work may enable—at least in part—a meaningful understanding of this challenging subject. This transformation of meaning may indeed facilitate a rethinking of the nature of substance.

Chapter 20 takes what we have learnt and raises it to a higher level. When I first started this work I was told by the Goethean phenomenologist Dick van Romunde that I should meditate on the harmony of the spheres. This Pythagorean Idea lies at the heart of chemistry, the nature of chemical elements, and their transmutation.

Chapter 21, our concluding chapter, draws everything together. It is a review of our journey towards a rethinking of the nature of substance, chemical elements, and the so-called atom. Mention will also be made here of other aspects so far omitted, such as homeopathy, water, cosmic influences, and spiritual beings. We are still a very long way away from an understanding of the phenomenon of biological transmutations. Much more practical research is required—to be able “to [completely] tame the materialistic lion”. Therefore practical recommendations are also given here for any future studies of this most challenging of phenomena—the alchemy in life processes. This chapter gives an overview of biodynamics and why a detailed conception of the nature of substance is required. Also, wider considerations for future experimental research will be discussed.

1. Steiner ([1924] 1993: pp. 102–103).

2. This is clearly an alchemical reference; see Hauck (2008).

3. Steiner ([1924] 1993: pp. 102–103).

4. See Chapter 8: Vitalism and the Hypothetical Nineteenth Century Atom.

5. See Chapter 13: Crossing the Threshold 1: Gravity, Electro-magnetism and the Taming of the Atom.

6. See Chapter 16: Rudolf Steiner – Spiritual Science, the Four Ethers and the Geometry of Space.

7. Unger ([1978] 1982/3: p.2 and supplement).

8. Newburgh, et al (2006), and especially Psillos (2011).

9. Rutherford (1908).

10. See Chapter 9: Herzeele, Preuss, Hauschka and Baumgartner – Can Plants Create Minerals?

11. See Chapter 10: Pictet, Baranger, Kervran and His Theoretical Mechanism.

12. See Chapter 11: Holleman and Biberian.

13. See Chapter 12: Vysotskii & Cold Fusion – Elements, Isotopes and Quantum Physics.

14. Antoine Lavoisier (1778) Elements of Chemistry In a New Systematic Order, Containing all the Modern Discoveries, Translated by Robert Kerr: http://infomotions.com/sandbox/great-books-redux/corpus/html/elements.html

15. See Rudolf Steiner’s 5th Agriculture Lecture.

16. Ramberg, Peter J. (2000) The Death of Vitalism and the Birth of Organic Chemistry: Wohler’s Urea Synthesis and the Disciplinary Identity of Organic Chemistry, AMBIX, Vol. 47, Part 3, November 2000.

17. See Chapter 15.

18. “Aldrich and Nier (1948) first demonstrated that 40Ar was the product of the decay of 40K.” From: Simon Kelley (2002) K-Ar and Ar-Ar Dating, Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry (2002) 47 (1): 785–818: https://www.geo.arizona.edu/~reiners/geos474-574/Kelley2002.pdf

19. Mallove, Eugene (2000) ‘Book Review: Biological Transmutations by C. Louis Kervran’ Infinite Energy, 34: 56. https://www.infinite-energy.com/iemagazine/issue34/bookreview_biotrans.html

20. Wim Holleman’s work inspired the creation of the Professor Dr. L.W.J. Holleman Stichting — the organisation which commissioned the writing of this book. It was created after his death in 1994 to encourage and support further research and understanding of his biological transmutation interests. See http://www.holleman.ch for details.

21. This is an Aristotelian concept, though he may well have discovered this truth himself (Zemplén, Gábor Áron, “Structure and Advancement in Goethe’s Morphology.” Marking Time: Romanticism and Evolution, edited by Joel Faflak, University of Toronto Press, Toronto; Buffalo; London, 2017, pp. 147–172: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctt1x76gzb.11. Accessed 20 July 2020).

22. Edward E. Tazer-Myers (2019) Rudolf Steiner’s Theory of Cognition: A Key To His Spiritual-Scientific Weltanschauung, PhD Thesis, Pacifica Graduate Institute:

https://www.proquest.com/openview/c548a64b7da04bbb488ab26889620446/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

23. One might say that projective geometry is the Universal geometry, at the heart of all possible geometries, including the Euclidean geometry which describes our physical three-dimensional space, the curved spacetime of Einstein, and the negative- or counter-space proposed by Steiner and used to understand the non-material etheric realms explored in Chapters 17-21.