This outline includes the worldviews (including what Steiner called moods and tones) discussed in my previous post.

Preface

Why I believe this book is important for me to write (and for others to read).

Prologue: Rethinking the Nature of Substance

Special worldview tone – Anthropomorphism – Personal meanings: In a special, single case a person takes all the world-pictures to some extent, restricting themself to what they can experience on or around or in themself. … In regard to world-outlooks they can reckon only with what they can find in themself.1

In which I introduce the main themes of the book: Biodynamics and Rudolf Steiner’s indications for a hidden alchemy in living processes; The taming of the atom – a sub-natural phenomenon; Biological transmutation of chemical elements and the requirement for a new Goethean scientific worldview.2

In Part I: The development of realism by Plato and Aristotle – physical matter and ideal spirit as two aspects of a single reality – our required worldview;3 contrasted with a mechanistic dualism of hypothetical atoms (moving in a void) and an external spirit capable of logical reasoning, which enabled mathematical physics and eventually led Lavoisier to develop his conservation law of matter, forbidding the transmutation of chemical elements.4

| The ideas introduced here are important for an understanding of the final part of the book. The term realism has unfortunately been used by many different people in many different ways. I have used it to represent a belief that both Universal Ideas (Plato’s forms), and material entities (physical objects) have an existence independent of our conscious or unconscious awareness, and that reality consists only in their holistic unity. However, the term has been used by others to represent other ideas: – Naive realism; – Rudolf Steiner, in his lecture series Human and Cosmic Thought (Der menschliche und der kosmische Gedanke, GA 151), used the term realism in the sense of naive realism – that only that which we are aware of based on our physical senses – i.e. material objects – exist independently of us. This has also been called objective reality. – Extreme realism or Platonic realism; – Represents a belief that only Ideal forms are real. This a view held by Neo-Platonists. I have become convinced that Plato himself didn’t actually believe in such an extreme view. However, he made it easy for people to believe that he did though, because, like Steiner, he wished to guard against a belief in naive realism. – Strong, moderate, metaphysical, immanent or Medieval realism; – Has been used to characterise the worldviews of Aristotle, Goethe (and by implication Steiner), as well as (somewhat controversially) Plato. – Arithmetical realism; – This was a view most famously held by Pythagoras, that all is number. – Transcendental realism; – I leave the meaning of this as an optional exercise for the reader! Rudolf Steiner contrasted (strong) realism with the predominant belief amongst scientists today of nominalism – a form of materialism, in which Ideas (Universal spiritual forms) are merely convenient names to describe the properties of objects which, it is supposed, have no existence outside of the individual mind of the philosopher or scientist. |

Part II follows nineteenth and early twentieth century science as it crosses the threshold from nature to sub-nature; both the existence of the atom and chemical substance as a dynamic entity are proven. It is acknowledged by academic scientists that their mathematical theories used to model such behaviours have no physical meaning.5

They almost exclusively believe that low energy nuclear reactions (such as those enabled by living organisms) are impossible. The few that do believe in low energy nuclear transmutation have failed to reach any consensus about how they might occur.6

Part III shows how a way forward towards a meaningful understanding may be developed. Rudolf Steiner, based on the worldview of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, gave indications as to how projective geometry, combined with his own conception of four Ideal, spiritual, etheric realms, dually linked with the four physical, material, classical elements, could be used to develop a meaningful understanding of the world that we inhabit – including both living and physical, material processes.

As a consequence we will discover how the strange sub-natural realms of what academic physicists attempted to describe using the meaningless mathematics of quantum mechanics and of Einstein’s theory of relativity – explored in the previous part of this book – become a meaningful part of the behaviour of chemistry, biology, gravity, light and nuclear phenomena. This leads us to a rethinking of substance. The Anthroposophist George Adams provisionally called the subject of his research Goethean mathematical physics.

This third part of the book also explores other aspects of Rudolf Steiner’s worldview. The behaviour of animals, and ourselves as human beings, requires an understanding of further linked realms – the physical, etheric, astral and ego. The influence of the planets and constellations – the harmony of the spheres – will be considered.7

Part I: Genesis – On Generation and Corruption

Soul tone – Theism – Seeking revelation in creation.8

In which the historical foundations of philosophy and science are introduced. The title is from Aristotle’s book, On Generation and Corruption, in which he considers genesis, or the holistic process of change, which is generally translated as coming to be, but may equally apply to a passing away. This was based on the concept of reality consisting of a unity of both matter (physical parts) and forms (ideal wholes) in which change involves a continuity either of matter or form. Against this was a mechanistic theory of atoms and void, in which change merely involves the rearrangement of atoms in space. Allegedly Plato found such ideas promoted by Democritus so ‘corrupt’ that he wished to destroy all of his books. Nevertheless, it is from the latter theory that modern academic science has developed.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe famously said that;

The history of science is science itself. … we attempt in vain to express the inner nature of a thing. We experience only effects, and a full history of these effects comprises the essence of the thing.

This book is an attempt to do just this – to have the possibility of encountering the experienced effects of the forces and entities which form the worldview of Goethe and Steiner from as wide an historical perspective as possible. In this way we might experience some of these effects ourselves with new eyes and thus the possibility of a higher, authentic encounter with the Ideal substance, or essence of the material phenomena we observe in living organisms.9

Lions are important symbols… Chemically the lion is any fixed substance obtained from the metals… Philosophically, the Green Lion is the raw forces of nature or the subconscious that we are seeking to tame.

Hauck (2008)

A green lion marks the starting point of life’s transformations.

Sanders (2020)

Chapter 1: The Search for Plato’s Philosopher

World-outlook mood – Occultism – Knowledge beyond us – Enquire: (willing) Question the reality presented by sense-perception and ordinary cognition.10

In which we are guided by Mary Louise Gill’s book, Philosophos, in a search for Plato’s elusive Philosopher. Like Plato’s students before us, the knowledge and abilities acquired in our search in this first chapter are exactly those which are required to develop an understanding of Plato’s Philosopher. In the course of our search we become Plato’s Philosopher. The clues are to be found in a trilogy of books formed by the Theaetetus, Sophist, and Statesman, and by way of an introduction, the Parmenides. I believe that it is no coincidence that the fundamental holistic worldview taught by Plato is essentially the same as that of Goethe and Steiner. The task is very much to “question the reality presented by sense-perception and ordinary cognition“.11

Chapter 2: The Paradox of Reality; The Unity of Matter and Ideal Substance

World-outlook mood – Transcendentalism – Hidden outside of us – Aspire: (feeling) Desire to transcend ordinary experience, seeking higher truths and ideals to gain a more profound understanding of reality.

In which we explore Aristotle’s further development of Plato’s concepts regarding the holistic nature of reality and his centrally important concept of ousia, which is most commonly translated into English as substance. I also intend to show how Aristotle taught how we acquire knowledge of the world and how this differs from the communicating to others of what we already know. Again, it is important to be aware that most academic and popular accounts of Aristotle misunderstand him because modern analytic thinking is incapable of dealing with the apparent paradox of a unity of matter and ideal form. It was Aristotle’s conception of element and substance that found its way into modern chemistry – though in a much changed form. Writers who have helped me develop a holistic understanding include Henri Bortoft, Mary Louise Gill, Joe Sachs and Jakob Ziguras.12

Chapter 3: Moral Philosophy

World-outlook mood – Mysticism – Inward seeking for divine – Reflect: (thinking) Turn inward to explore inner experiences and uncover deeper truths that are not accessible through external observation.

In which I move out of my comfort zone and learn how Christian and Islamic theology replaced my beloved philosophy. Plato and Aristotle took thinking as far as they could. So what of our doings? How do we live a good life? Plotinus and Late Classical philosophy – theological developments – Christian scholastic developments lead to nominalism, mechanistic science.13

Chapter 4: Nominalism: Elements, Atoms and Change

World-outlook mood – Empiricism – External Knowledge – Perceptualize: (percept) Gather knowledge through direct experience and observation of the external world, forming understandings based on empirical data and observable phenomena.

In which I show that while Plato and Aristotle were developing a synthetic (as in synthesis, not artificial), holistic insight, other Classical Greek philosophers, such as Democritus, were developing analytic, mechanical theories, involving hypothetical atomistic, or corpuscular theories. Both theories attempted to bridge the paradoxes involved in attempting to unify the ideal and material perspectives of the world. Such mechanistic, atomistic theories were most famously promoted in the epicurean epic poem, De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things) by the Roman Epicurean philosopher, Lucretius. When it was rediscovered during the Renaissance, it heavily influenced mathematical scientists such as Descartes. Philosophically the rise of nominalism led to a dehumanising of the world, limiting the spiritual to heavenly matters.14

Chapter 5: Alchemy, Medicine and Mysticism

World-outlook mood – Voluntarism – Will – Conceptualize: (concept) Understand the world through the lens of willpower and intention. Conceptualize the forces and principles that shape reality.

In which I show that the alchemical ideas most famously promoted by Paracelsus were prevalent during the Renaissance, despite what many modern histories of science would have us believe. It was more than just the name that modern chemistry inherited. Its concepts influenced influential people Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton, Goethe, Rudolf Steiner and many others of importance to this book. The human being as an active participant in observation is important.15

Chapter 6: Renaissance Science and the Ghost in the Machine

World-outlook mood – Logicism – Making connections – Individualize: (idea) Find logical connection of thoughts, concepts, and ideas. Individualize concepts forming structured ideas.

In which I show how Copernicus, Galileo, Descartes and Newton, amongst others, were responsible for the development of mathematical physics, and its later importance.16

Chapter 7: Revolution – Quantitative Chemistry

World-outlook mood – Gnosis – Sense free knowledge – Realize: (reality) Achieving a deep, intuitive understanding and cognitive fulfilment, gaining profound insights through inner cognitive forces, integrating knowledge into a holistic comprehension of truth.

In which the importance of the development of quantitative chemistry is discussed, in particular the work and ideas of Lavoisier. Chemistry started moving forward away from its Aristotelian and alchemical roots from Renaissance times. Jan Baptist Van Helmont was a disciple of Paracelsus who nevertheless believed in the new learning based on experimentation. Shortly afterwards was Robert Boyle whose revolutionary book, The Sceptical Chymist, led to him being called by some the founder of modern chemistry because of his corpuscular (atomic) ideas. His ideas presupposed a conservation law of matter – possibly taken from the writing of Empedocles.

Lavoisier is most famous for what he considered to be definitive experimental proof of the conservation law of matter. He is of particular interest to this book for it was this conservation law which helped set the foundations for an analytical, atomic chemistry. It was also what those who believed in the biological transmutation of elements rallied against.17

This ends the first part of the book.

Part II: Crossing the Threshold – Atom, Isotope and Transmutation

Tone – Intuitionism – Seeking revelation from intuition

In which material science transcends its own boundaries.

Lions are important symbols … Chemically the lion is any fixed substance obtained from the metals … Philosophically … the Red Lion is the assimilation or control of those forces…

Hauck (2008)

A red lion stands for your eternal wish to achieve enlightenment.

Sanders (2020)

Chapter 8: Vitalism and the Hypothetical Nineteenth Century Atom

World-outlook mood – Occultism – Knowledge beyond us – Enquire: (willing) Question the reality presented by sense-perception and ordinary cognition.

In which I show how in the early decades of the nineteenth century, despite the advances of knowledge based on a hypothetical ‘material’ atom, vitalism was still considered a possibility by many well respected chemists. The most famous was Berzelius. The experiments of Wiegmann and Polstorf, which were supposed to be conclusive proof that living organisms were incapable of the transmutation of chemical elements, Holleman showed were far from conclusive.

Evidence for the atom was based on the patterns of behaviour of chemical substances and their reactions. Although physical evidence for proportional relationships was observed, it should be remembered that the nineteenth century atom was an entirely hypothetical creation of the mind. However, this theoretical concept gained considerable support during the course of this century:

- 1789 – Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier in his Traité Élémentaire de Chimie (Elementary Treatise of Chemistry);

- Defined the law of conservation of mass;

- Defined chemical element and listed all those known to him and classified them as metals or non-metals.

- 1794 – Joseph Proust, French chemist;

- Law of definite proportions.

- 1803, 1808 – John Dalton collected the results of quantitative analyses of chemical compounds and developed a law of multiple proportions;

- 1811, 1813 – Amedeo Avogadro;

- Avogadro’s law, provided a method for deducing the relative weights of the molecules of gaseous elements;

- 1813-14 – Jöns Jakob Berzelius

- 1815, 1816 – William Prout, English chemist;

- Published lists of all known atomic weights and hypothesised that chemical elements are all multiples of the hydrogen atom, the protyle.

- 1817 & 1829 – Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner, a German chemist;

- Döbereiner’s triads were based on observation that many of the 53 then known elements formed groups of three.

- 1826 – Jean-Baptiste Dumas, French chemist;

- 1863, 1865 – John Newlands, British chemist;

- 1864, 1870 – Julius Lothar Meyer

- 1869 – Dmitri Mendeleev

- 1944 – Glenn T. Seaborg

Others, such as the German chemist Ostwald strongly disagreed with such a hypothetical concept. Nevertheless, based on this concept, the behaviour of solids, liquids and gasses was accounted for.18

Chapter 9: Herzeele, Preuss and Goethe – Living Earth

World-outlook mood – Transcendentalism – Hidden outside of us – Aspire: (feeling) Desire to transcend ordinary experience, seeking higher truths and ideals to gain a more profound understanding of reality.

In which I show how, despite the conservation law of matter, Baron von Herzeele, was inspired to prove his belief that it is the plant that makes the soil. His inspiration was from the ideas of Goethe, which was written about by the philosopher Wilhelm Heinrich Preuss in his book Spirit and Matter. He believed that everything in the Universe, including living beings, is connected. The problem of life is the problem of the universe. Rudolf Hauschka found just one surviving copy of Herzeele’s biological transmutation research, The Origin of Inorganic Substances, which involved over 500 chemical analyses of germinating seeds conducted between 1876 and 1883. Hauschka quoted Herzeele as saying that “dead matter is never of primary origin. ‘What lives may die, but nothing is created dead’, and ‘the soil does not produce plants; plants produce soil. Preuss speaks of these experiments as follows: ‘Herzeele’s experiments offer tangible proof that the supposed immutability of chemical elements is a fiction that must be speedily discarded if natural science is to progress. … ‘Wherever lime or magnesium are found, a plant must have lived and produced these substances’ says Herzeele. ‘The first milligramme of lime is no older than the first plant’.”

Rudolf Hauschka’s own biological transmutation experiments were inspired by Herzeele. His experiments related to the new-forming of matter from spirit. Stephan Baumgartner attempted, but failed, to replicate his results.19

Chapter 10: Pictet, Baranger, Kervran and His Theoretical Mechanism

World-outlook mood – Mysticism – Inward seeking for divine – Reflect: (thinking) Turn inward to explore inner experiences and uncover deeper truths that are not accessible through external observation.

In which I show that there were two independent paths to the investigation of the transmutation of chemical elements. The path from Herzeele, who believed in the Goethean worldview we looked at in the previous chapter.

The other came from anomalous (unexpected) observations made by mainstream academic scientists. Pictet and Freundler were examples of these.

The Frenchman Corentin Louis Kervran, collected all of these studies, and many others as well. More than anyone else he promoted the subject of the biological transmutation of chemical elements. In part this was because his theoretical mechanism was a simple one. Unfortunately his scientific credibility was very poor. He demonstrated no critical faculty when it came to either experimental design or analysis of results.20

Chapter 11: Holleman and Biberian’s Experiments

World-outlook mood – Empiricism – External Knowledge – Perceptualize: (percept) Gather knowledge through direct experience and observation of the external world, forming understandings based on empirical data and observable phenomena.

In which I show the thoughts and results of someone in whose work I have great trust. The Dutch analytical chemist L.W.J. (Wim) Holleman conducted a series of experiments which showed the disappearance then reappearance of potassium in cultures of algae. Sadly he was unable to continue his research in order to replicate his results. He considered his results to be provisional, and didn’t wish to formally publish until they had been replicated, not once but several times.

After his death I translated, completed and published on Internet the unfinished report of his results. I was unable to find any error in his methodology, though agreed that his results should only be considered provisional. As a result of my publication the French physicist Jean Paul Biberian, working in collaboration with a chemist and a biologist, made a second provisional experiment with similarly extraordinary results.21

Chapter 12: Vysotskii & Cold Fusion – Elements, Isotopes and Quantum Mechanics

World-outlook mood – Voluntarism – Will – Conceptualize: (concept) Understand the world through the lens of willpower and intention. Conceptualize the forces and principles that shape reality.

In which I show how the Ukrainian nuclear physicist, Vladimir Vysotskii, has consistently produced the only biological transmutation results which I consider to be definitive. Like both Holleman and myself, he was also critical of the publications of Kervran. Like Biberian, he is also involved in what is popularly known as cold fusion. Vysotskii’s experiments proved that the chemical element transmutations which he observed were nuclear transmutations of chemical isotopes. However, these were not high energy transmutations. Though such low energy transmutations are not recognised by mainstream science, Vysotskii believes that his research demonstrates that such under-researched phenomena are capable of being explained by the latest developments in quantum theory. This is a mysterious realm which lies beyond the threshold of physical matter.22

Chapter 13: Crossing the Threshold 1: Gravity, Electro-magnetism, Light and the Nuclear Atom

World-outlook mood – Logicism – Making connections – Individualize: (idea) Find logical connection of thoughts, concepts, and ideas. Individualize concepts forming structured ideas.

Spooky action-at-a-distance phenomena such as gravity have been a challenge to those who believe in a mechanical universe. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz complained that the mechanism of gravity was “invisible, intangible, and not mechanical.” His contemporary, Isaac Newton said considered action at a distance to be “so great an Absurdity that I believe no Man who has in philosophical Matters a competent Faculty of thinking can ever fall into it.” The attractive powers of static-electricity charged objects such as amber were well known since ancient times. Magnetism was less well known but showed many characteristics common to both. The Elizabethan physicist, William Gilbert, made many new observations regarding both electricity and magnetism. However he is quoted as saying “no action can be performed by matter save by contact” despite there being evidence for just that.

By the mid-eighteenth century Franz Aepinus and shortly after Henry Cavendish independently conducted experiments which led them to both to consider that electricity and magnetism existed in a reciprocal relationship. He developed a mathematical model of electrostatic induction that relied on action at a distance. However, like Newton with gravity, he believed that in actuality the transmission of force required contact.

Their work was further developed by the experimental genius, Michael Faraday. He conducted further experiments which he visualised – for the first time – as electrical and magnetic fields of force. The interactions between the two were observed to generate high frequency oscillations, these ‘waves’ were imagined to be transmitted by means an unknown fluid. This hypothetical fluid was called the luminiferous ether, not to be confused with the ethers of Rudolf Steiner.

Newton mathematically described the actions of gravity. Einstein later developed his theory of curved space-time (special relativity) which again only accounts for the actions of gravity and not what it is – its true nature remains a mystery to academic science (see chapter 18).

Faraday, Crookes and Thomson, etc – see Lehrs. Crookes and Thomson, like many of their contemporaries, were interested in the paranormal – the radiant electrical phenomena they were investigating were very much from a mysterious realm. Following on from this, Henri Becquerel and Marie Curie discovered radioactivity, indicating that atoms were not indestructible.23

Chapter 14: Crossing the Threshold 2: Thermodynamics and Quantum Mechanics

World-outlook mood – Gnosis – Sense free knowledge – Realize: (reality) Achieving a deep, intuitive understanding and cognitive fulfilment, gaining profound insights through inner cognitive forces, integrating knowledge into a holistic comprehension of truth.

In which it is shown how the mechanical model of thermodynamics, which was based on the movement of hypothetical atoms, lead to unexpected experimental results relating to the light emissions of heated objects. The latter could only be explained by a series of discrete emissions, which were named quanta (plural of quantum). However, such phenomena were unexplainable based on classical (material) physics. Nevertheless, the mathematics used were borrowed from mechanical models of invisible particles. Therefore this new study of such non-material phenomena was named quantum physics.

Part III: Sublimation – Rudolf Steiner, Life and the Possibility of a Goethean Physics

Worldview tone – Naturalism – Seeking revelation in Nature

In which the nature of substance is rethought and how matter, life and nuclear transmutations may be united by way of a person-centred Goethean Physics.

Lions are important symbols … Chemically the lion is any fixed substance obtained from the metals … Philosophically … in the final stages of the work, the Red Lion grows wings. The Winged Lion is the volatile or spiritual aspect of a substance, which is the sublimated salt used to make the Philosopher’s Stone.

Hauck (2008)

Dreams with winged lions are suggestive of forthcoming better times.

Sanders (2020).24

Chapter 15: Goethean Worldview – Phenomenology and Hermeneutics

World-outlook mood – Occultism – Knowledge beyond us – Enquire: (willing) Question the reality presented by sense-perception and ordinary cognition.

In which I explore Goethe’s worldview, which was the foundation of the philosophical and scientific ideas of Herzeele, Holleman and Rudolf Steiner. Steiner and Henry Bortoft are important guides, amongst others.25

Chapter 16: Rudolf Steiner – Spiritual Science, the Four Ethers and the Geometry of Space

World-outlook mood – Transcendentalism – Hidden outside of us – Aspire: (feeling) Desire to transcend ordinary experience, seeking higher truths and ideals to gain a more profound understanding of reality.

In which I examine Steiner’s worldview, including his introductory theosophical view of the human being as body, soul, spirit and ego. I also consider his ideas about the atom, ethers and projective geometry. The PhD thesis about his worldview by Edward Tazer-Myers may be of help.26

Chapter 17: George Adams – Projective Geometry and Ideal Space

World-outlook mood – Mysticism – Inward seeking for divine – Reflect: (thinking) Turn inward to explore inner experiences and uncover deeper truths that are not accessible through external observation.

In which I examine Steiner’s indications for projective geometry as furthered by George Adams as means of developing a Goethean physics.27

Chapter 18: Projective Geometry and the Etheric – Life Between Earth and Sun

World-outlook mood – Empiricism – External Knowledge – Perceptualize: (percept) Gather knowledge through direct experience and observation of the external world, forming understandings based on empirical data and observable phenomena.

Centred around the artistic interpretation of Olive Whicher as a result of her collaboration with George Adams. Works such as The Plant Between Sun and Earth and Projective Geometry – Creative Polarities in Space and Time are my inspiration here.

After reading Glen Atkinson’s The Problem of the Etheric Formative Forces, I feel it is important to place here some of the many ideas different Anthroposophists have regarding the four ethers and formative forces in general. Jochen Bochenmuhl, Karl Koenig, Ernst Lehrs, Bernard Lievegoed, Ernst Marti, Hermann Poppelbaum, Paul Schiller, many references by Rudolf Steiner, Gunther Wachsmuth, Ita Wegman, and many others have made contributions, many of which are seemingly contradictory. Just what principles do they all hold in common? What can we learn from them?28

Chapter 19: Nick Thomas – Science Based on a Linked Space and Counterspace

World-outlook mood – Voluntarism – Will – Conceptualize: (concept) Understand the world through the lens of willpower and intention. Conceptualize the forces and principles that shape reality.

Based on the publications of Nick Thomas – introduces the basic principles of his development of the work of George Adams. His first challenging finding was a new understanding of gravity.29

Chapter 20: Nick Thomas – Working Towards a Goethean Mathematical Physics

World-outlook mood – Logicism – Making connections – Individualize: (idea) Find logical connection of thoughts, concepts, and ideas. Individualize concepts forming structured ideas.

In which I admit to having been shocked to discover that many of the scientifically challenging ideas of Rudolf Steiner, which appear to contradict both Einstein’s general theory of relativity (the speed of light being instantaneous and not constant) and quantum mechanics, are shown to be capable of meeting the otherwise unexplained observations which required Einstein to develop the purely mathematically based ideas which he spent most of his later life trying to overcome. In my opinion Nick Thomas may have successfully given meaning to mathematical physics.

His independent derivation of Schroedinger’s wave equation, which lies at the heart of the mainstream understanding of atomic behaviour, demonstrates that musical harmony is very part of the behaviour of the chemical or tone ether.30

Chapter 21: Rethinking The Nature of Substance and the Harmony of the Spheres; Life, Transmutations, Ethers and Astral Forces

World-outlook mood – Gnosis – Sense free knowledge – Realize: (reality) Achieving a deep, intuitive understanding and cognitive fulfilment, gaining profound insights through inner cognitive forces, integrating knowledge into a holistic comprehension of truth.

In which I draw all the threads together – how an understanding of the phenomenological hermeneutic worldviews of both Aristotle and Goethe, linked with Steiner’s proposal to use projective geometry to mathematically describe his concept of an ideal etheric space, the dual opposite of physical, point centred space, can be used to produce a person-centred Goethean mathematical physics. Nick Thomas demonstrated the possibilities of such a project.

Tying in their work with that of Vladimir Vysotskii’s studies of low energy nuclear transmutations of chemical isotopes enabled by living organisms, has suggested to me that Steiner’s life ether is responsible for this phenomenon, though working in conjunction with the chemical ether.

But what of life outside the laboratory? When I asked the Anthroposophical phenomenological scientist and friend of Wim Holleman, Dick van Romunde for advice on where to seek inspiration on this subject he told me to meditate on the harmony of the spheres. Life is dynamic and influences and is influenced by many forces, both outside and within. This book has emphasized material and etheric forces. However, the work of both Maria Thun and Lawrence Edwards have demonstrated that planetary forces – the astral – also play their part.

The essential nature of water for the chemistry of life and chaos as a creative agent, as revealed by John Wilkes and others should be considered. As well as homeopathic potentization (see lecture by George Adams, and Ernst Marti).

Both biodynamics and Anthroposophical medicine require deeper understandings of their fundamental workings. The consequences of all these considerations on experimental design is something that should be explored here.31

Epilogue: New beginnings

Worldview Mood – Anthropomorphism – Personal meanings

In which I share what the above personally means to me.

Footnotes

1. See https://en.anthro.wiki/Worldview; Steiner (1914b | 1991) Human and Cosmic Thought; Last (2024) Worldview Thought Structure Of The Philosophy Of Freedom: https://philosophyoffreedom.com/profiles/blog/worldview-thought-structure-of-the-philosophy-of-freedom.

2. See Steiner, 5th Agriculture lecture, 13 June, 1924 Koberwitz, GA 327: https://rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA327/English/BDA1958/19240613p01.html. See also Section 10 of Holleman, Review of Research on the Biological Transmutation of Chemical Elements; Critical Discussion of Holleman’s Chlorella Research: http://www.holleman.ch/h_s10.html.

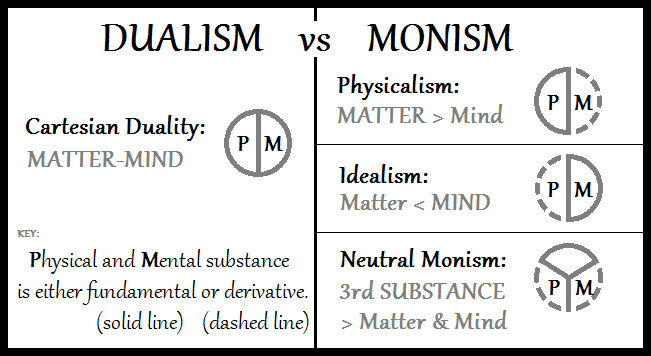

3. As far as I am aware Rudolf Steiner only related his own beliefs to those of the nineteenth century German philosophers with which his audience may have been familiar. Like Plato, his main concern was to guard against materialistic naive materialism and nominalism. Therefore, in the sixth chapter of Goethes Naturwissenschaftliche Schriften, Einleitungen (Goethean Science GA001: https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA001/English/MP1988/GA001_c06.html) Steiner identified his beliefs with objective idealism. This might imply a belief in the independent existence of Universal Ideas, such as is in line with platonic (extreme) realism. However this is only one aspect of his philosophical beliefs. The other relates to the unity of both physical percept and Ideal concept. Rudolf Steiner, in the same book, demonstrated the central importance of this unity for Goethe’s worldview. Steiner characterises such a worldview in his Philosophie der Freiheit, as monism. Again, as the diagram above shows, there are several kinds of monism. Such a monism has characterised as a dual or binary monism and which is identified in the diagram below as neutral monism. I can therefore confidently place him as a strong or immanent realist, in line with Aristotle, (controversially) Plato, some Medieval scholastics, Goethe, and possibly the phenomenological and hermeneutic philosophers such as Husserl, Heidegger and Gadamer.

For whatever reasons, few realists have described themselves as such and most philosophical writing on realism has been against the beliefs of others. Whatever we believe is real, is something that we normally take for granted as true; it lies at the unspoken foundation of our worldview. This is why I believe it is important. This process of change, an altering of the foundations of my own beliefs is hard. I was a naive realist. A materialist scientist. Intellectually I have discovered that such a belief is untenable. The strong realism of Plato, Aristotle, Goethe, Steiner and many, many others, based on my research, appears to be the most logically coherent alternative. I therefore want to change my belief. But unlike Goethe I have no inner intuition of a linked matter and spirit, no inner certainty if this is true. The foundations of my new worldview are mere gossamer thin threads of logic, held together by a intermittent inner warmth of soul. Parmenides wrote that he was guided by the goddess Aletheia. Heidegger, in Parmenides, wrote that she was truth, in the sense of disclosure, unconcealment. Christopher P. Long revises that description;

the question of truth has always been rooted in human[s] being together even as it increasingly came to designate the dynamic relationship between human beings and the things they encounter. … aletheia can be heard to name the attempt to articulate things as they show themselves to be. … But aletheia has always involved the human and, more specifically, it does not point the neutral and abstract happening of being; rather, aletheia is the site of the human encounter with being, that is, to the site of self-concealing appearing.

Late Heidegger and Aletheia

By Christopher Long, September 5, 2009

Perhaps, in the course of researching and writing this book – in my attempt to articulate things as they show themselves to be – Aletheia may reveal herself to me.

Goethe, in “Erläuterung zu dem aphoristischen Aufsatz ‘Die Natur’” (1828; Explanation on the Aphoristic Essay “Nature”) succinctly expressed this unity of matter and spirit as:

…matter can never exist and have an impact without spirit, nor spirit without matter…

He also summed up the philosophical conundrum of the unity of two-ness that is reality in a verse he titled Gingo Biloba (a tree which has bi-lobed leaves);

To my garden here translated,

Foliage of this eastern tree

Nourishes the initiated

With it’s meaning’s mystery.

Is its leaf one self divided,

Forked into a shape of strife?

Or have two of them decided

On a symbiotic life?

This I answer without trouble

And am qualified to know:

I am single, I am double,

And my poems tell you so.

Translator as yet unknown.

Henri Bortoft, in Chapter 3 (pp. 77-107) of The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe’s Way Toward a Science of Conscious Participation in Nature gave more detailed insights into these Ideas which are essential to an understanding of this book.

For more information see, for example,

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on Universals

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy lists only seven varieties of realism – there are many others!

- Philosophical realism: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophical_realism

- Moderate realism: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moderate_realism

- Scotistic realism: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scotist_realism

- Transcendental realism: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transcendental_realism

- Not to be confused with F. W. J. Schelling’s transcendental realism (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transcendental_realism_(Schelling)), Arthur Schopenhauer’s transcendental realism (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transcendental_realism_(Schopenhauer)), or Julius Evola’s transcendental realism (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transcendental_realism_(Evola))!

- For my Goethe and Steiner references see:

- Jennifer Caisley (2022) Materie (Matter), Goethe-Lexicon of Philosophical Concepts, Vol. 3 (2022): Third Installment: https://goethe-lexicon.pitt.edu/GL/article/view/60.

4. See Lehrs (1985) Man or Matter; Bortoft (1996) The Wholeness of Nature; and Dijksterhuis (1969) The Mechanization of the World Picture.

5. See Lehrs (1985) Man or Matter; Unger (1978 | 1982/3) On Nuclear Energy and the Occult Atom; and Francis (2012) Steiner and the Atom.

6. See Vysotskii and Kornilova (2010) Nuclear Transmutation of Stable and Radioactive Isotopes in Biological Systems; Holleman (1982 | 1999) A Review of Research on the Biological Transmutation of Chemical Elements: http://www.holleman.ch/holleman.html; and Biberian (2012) Biological Transmutations: Historical Perspective, Journal of Condensed Matter Nuclear Science, 7, 11–25: https://jcmns.scholasticahq.com.

7. If true, some widely held concepts within the Anthroposophical world – such as the nature of gravity – may need to be reconsidered. However, it also means that other ideas held by Anthroposophists, but generally disbelieved by mainstream academic science, such as biodynamic agriculture and Anthroposophic medicine, would now have a stronger reason for support and grounds for further research.

The best overview of Anthroposophical science (primarily written for a medical audience) is Heusser, Peter (2016) Anthroposophy and Science: An Introduction, Peter Lang (publ.). Several excellent reviews are available online, such as, Ricardo R. Bartelme (2017) Anthroposophic Medicine, an Introduction; and a Book Review of Anthroposophy and Science, Integrative Medicine (Encinitas). 2017 Aug; 16(4): 42–46: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6415628/. A number of reviews of biodynamic research have also been published and the majority demonstrated positive benefits on a purely empirical basis. An excellent recent example is one clearly written by a non-anthroposophist. Despite many of his claims about the beliefs of Rudolf Steiner and his Anthroposophical followers being extremely negative, he has clearly shown the positive results from a wide range of academic scientific studies and his conclusion is entirely in favour of the benefits of biodynamic farming in comparison to both organic and conventional systems; Muhie, Seid Hussen (2023) Concepts, principles, and application of biodynamic farming: a review, Circular Economy and Sustainability, 3 (1), 291-304: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-022-00184-8.

For an introduction to some of the theory and practice of biodynamics the Oregon BD website is the best that I know, though it encompasses some ideas which are outside of the core principles of Biodynamics – it is primarily based on Wolf-Dieter Storl’s Culture and Horticulture: The Classic Guide to Biodynamic and Organic Gardening, as well as the interesting ideas of Glen Atkinson: http://garudabd.org/books/ – Oregon BD Online Course: https://www.oregonbd.org/online-course.

Background reading for this part might include;

- Lehrs, Ernst (1985) Man or Matter, Rudolf Steiner Press.

- Steiner, Rudolf (1883-1897 | 1988) Goethean Science, GA001: https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA001/English/MP1988/GA001_index.html.

- Tazer-Myers, Edward E. (2019) Rudolf Steiner’s Theory of Cognition: A Key to His Spiritual-Scientific Weltanschauung, Pacifica Graduate Institute ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: https://www.proquest.com/openview/c548a64b7da04bbb488ab26889620446/.

- Thomas, Nick (1999) Science Between Space and Counterspace: Exploring the Significance of Negative Space, Temple Lodge Publications.

- Whicher, Olive (1971) Projective Geometry – Creative Polarities in Space and Time.

8. Refences include;

- Anthrowiki contributor (2021) Worldview: https://en.anthro.wiki/Worldview.

- Rudolf Steiner’s (1914b | 1991) Human and Cosmic Thought, GA 151: https://rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA151/English/RSP1961/19140121p01.html.

- Tom Last (2021) Worldview Thought Structure Of The Philosophy Of Freedom: https://philosophyoffreedom.com/profiles/blog/worldview-thought-structure-of-the-philosophy-of-freedom.

9. The choice of title was inspired by Mary Louise Gill’s (1991) Aristotle on Substance: The Paradox of Unity, in which she showed how Aristotle solved the paradoxical challenge of change in Parmenides’ concept of unchangeable Ideal existence in which all is one. He believed that his conception remained true to Nature. By contrast Democritus’ hypothetical atoms were an intellectual creation to solve the same question. An excellent introduction to the ideas of Democritus and their later consequences for Renaissance science is found in Dijksterhuis’s (1969) The Mechanization of the World Picture. For a Goethean understanding of my intended approach see;

- Goethe, JW von (1792 | 2010) The Experiment as Mediator of Object and Subject (Der Versuch als Vermittler von Objekt und Subjekt), translated with Goethe the Scientist and Self-Critic by Craig Holdrege, The Nature Institute, from In Context #24 (Fall, 2010): https://www.natureinstitute.org/article/goethe/experiment-as-mediator-of-object-and-subject;

- Talbott, Stephen L. (1998) Goethean Science: A Book Review, The Nature Institute: https://bwo.life/goethe.htm;

- Wise, M. Norton (2016) Goethe Was Right: ‘The History of Science Is Science Itself’, in: Alexander Blum, Kostas Gavroglu, Christian Joas and Jürgen Renn (eds.): Shifting Paradigms: Thomas S. Kuhn and the History of Science, Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge: Proceedings 8: http://mprl-series.mpg.de/proceedings/8/;

10. From, Tom Last (20th May 2024) Comparing the Scientific Method to Steiner’s 7 World-Outlook Moods (Whole Being Cognition): https://philosophyoffreedom.com/profiles/blog/comparing-the-scientific-method-to-steiner-s-7-world-outlook-mood.

11. This chapter also needs to include the importance of mathematics and geometry in Plato’s Academy. How this led to today’s concept of academic or academia – the educational institutions that are the gateways to what is considered to be acceptable knowledge and methodologies. For further reading, see;

- Anthrowiki contributors (2024) Science, Anthrowiki: https://en.anthro.wiki/Science;

- Bortoft, Henri (1996) The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe’s Way Toward a Science of Conscious Participation in Nature;

- Caswell, Matthew (2023) Philosophy and the Cave Wall: https://digitalarchives.sjc.edu/;

- Gill, Mary Louise (2012) Philosophos: Plato’s Missing Dialogue;

- Heidegger, Martin (1992) Parmenides;

- Plato (2007) Republic, Translated with introduction and glossary by Joe Sachs;

- Plato (2011) Socrates and the Sophists: Plato’s Protagoras, Euthydemus, Hippias major and Cratylus, translated with notes and glossary by Joe Sachs;

- Plato (2012) Theaetetus, Joe Sachs, editor, translator;

- Sachs, Joe (1992) The Battle of the Gods and the Giants, St. John’s College: https://digitalarchives.sjc.edu/items/show/3720;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1897 | 1928) Goethe’s Weltanshauung, translated as Goethe’s Conception of the World by Harry Collison, Anthroposophic Publishing Company, GA 006: Chapters 2-4: https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA006/English/APC1928/GA006_index.html;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1901 | 1983) Über Philosophie, Geschichte und Literatur: Vorträge an der Arbeiterbildungsschule in Berlin: Welt- und Lebensanschauungen von den Ältesten Zeiten bis zur Gegenwart: Berlin, Januar 1901: Die griechischen Weltanschauungen, (Lecture 1: The Greeks’ Worldview). Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach, Schweiz, GA 051: https://rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA051/English/SOL2023/19010107c01.html;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1904 | 1928) Philosophie und Anthroposophie. Gesammelte Aufsätze 1904–1918. Aufsätze und neun Auto-Referate nach Vorträgen in verschiedenen Städten (Mathematics and Occultism). An address delivered to the First Annual Congress of the Federation of European Sections of the Theosophical Society, Amsterdam, June, 1904. Translated by M. H. Eyre, edited by H. Collison. (From the Transactions of the Congress), GA 035: https://rsarchive.org/Articles/GA035/English/Singles/MatOcc.html;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1918c | 1985) Goethes Weltanschauung, translated as Goethe’s World View, by William Lindeman, Mercury Press, GA 006: https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA006/English/MP1985/GA006_index.html.

- Wikipedia contributors (2024) Academy, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academy.

- Wikipedia contributors (2024) Scientific Community, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_community.

12. References include;

- Bortoft, Henri (1996) The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe’s Way Toward a Science of Conscious Participation in Nature;

- Gill, Mary Louise (1991) Aristotle on Substance: The Paradox of Unity, Princeton University Press;

- Holmyard, Eric John (1931) Makers of Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press: https://archive.org/details/makersofchemistr029725mbp/;

- Sachs, Joe (1980) An outline of the argument of Artistotle’s Metaphysics: https://digitalarchives.sjc.edu/items/show/3726;

- Sachs, Joe (1995) Aristotle’s Physics: A Guided Study, Masterworks of Discovery, Kindle edition;

- Sachs, Joe (translator) (1999) Aristotle’s Metaphysics, Green Lion Press;

- Ziguras, Jakob (2011) Aristotle’s Rational Empiricism: A Goethean Interpretation of Aristotle’s Theory of Knowledge, PhD Diss., The University of Sydney.

13. Rudolf Steiner has written on the subject in several of his works: Goethe’s World View (Goethes Weltanschauung), GA 006; Riddles of Philosophy; (Die Rätsel der Philosophie), GA 018; and I am sure that he and others will provide further guidance, especially Max Leyf. For background guidance, Wikipedia and the English and German editions of the excellent AnthroWiki. [From memory,] Joe Sachs has written of how the original meaning of ousia, which was thinghood – that which makes a thing something special, its spiritual essence, by analogy with knighthood – became substance, something which lies under and not above. Spiritual entities after Augustine were reserved exclusively for heavenly beings, not earthly things. Since starting this project it has become my wish to reinstate everyday material entities as being something special. Imagine the joy experienced by the prisoner who escaped from the darkness of Plato’s cave – with its two-dimensional shadow world – into a light illuminated world possessing an extra dimension of ideal spiritual form. This is what early Christianity attempted to replace, not by adding a new dimension but by reserving the spirit for their own purposes and demoting what both Plato and Aristotle had seen in nature to that which lies under.

However, Rudolf Steiner indicated that such events enabled humanity to develop in new ways. Nature was deprived of her higher spirit. This enabled the natural sciences to develop materialistically. Apparently it was an important as part of a process, as a means to enable more positive ends. It enabled a quantitative science to develop which encouraged the further development of mathematics. Eventually, towards the end of the nineteenth century, it had reached the point when projective geometry was able to model the holistic natural worldview of Plato, Aristotle, Goethe and Steiner. Or so I hope.

I have a strong feeling that my limited understanding will change and develop during the course of my research. Plato’s belief in The One, the Form of the Good, described as an illuminating light, by Plotinus, which guided theologians and philosophers of Christianity, Islam and Judaism; Steiner’s teaching of the Mysteries in Christianity as Mystical Fact; and much more. They taught of yet higher dimensions regarding which even the Greek, Latin and Arabic languages may not have had the words.

It would be easy here to speak of my prejudice against most organised religions and the terrible politics of power and wars they have entailed (and still do). However, many years ago, I was taught by a wise old man in a pub the difference between faith and religion. Slowly my faith in something other, something greater than the teachings of mechanistic science has been developing. There has been no great flash of inspiration on the road to Damascus. I don’t know as yet what I believe. And, for now, that is ok.

Even relatively modern scientists, such as Max Planck the founder of quantum theory (the mathematical description of a strange sub-natural realm which is inexplicable to classical physics – see Chapter 14), have spoken openly about their beliefs in higher powers;

… so we must hypothesize a deliberate intelligent spirit behind this force [the force which causes both the universe and the atom to hold together]. This spirit is the foundation of all matter. A visible but not corruptible matter is real, true, authentic, because matter without the spirit cannot be — but the invisible, immortal Spirit is the reality! Also since a spirit cannot exist by itself, but every spirit belongs to an entity, we are forced to assume that there exist spiritual beings. However, since spirit beings cannot come into being by themselves, but must be created, so I am not shy to designate this mysterious creator, as him, whom all civilizations of the earth have called in earlier millennia: God! In this, the physicist, in dealing with the subject matter of the will, must travel from the kingdom of the substance to the realm of the Spirit. And so that is our task in the end, and we must place our research in the hands of philosophy.

Max Planck (in Das Wesen der Materie, a 1944 speech in Florence, Italy), quoted by Sarah Salviander (2015).

My references will include;

- Bortoft, Henri (1996) The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe’s Way Toward a Science of Conscious Participation in Nature, Lindisfarne Books;

- Dijksterhuis, Eduard Jan (1969) The Mechanization of the World Picture, Oxford University Press;

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (2013) Western Esotericism: A Guide for the Perplexed, Bloomsbury Academic;

- Leyf Treinen, Max (2020) The Redemption of Thinking: A Study in Truth, Knowledge, and the Evolution of Consciousness with Special Reference to Johann Von Goethe, Owen Barfield, and Rudolf Steiner, Amazon Digital Services, Kindle edition;

- Sachs, Joe (translator) (1999) Aristotle’s Metaphysics, Green Lion Press;

- Salviander, Sarah (2015) Planck’s logical argument for God, Six Day Science: Faith in Science | Science in Faith: https://sixdayscience.com/2015/10/15/plancks-logical-argument-for-god/;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1897 | 1928) Goethe’s Weltanshauung, translated as Goethe’s Conception of the World by Harry Collison, GA 006, Anthroposophic Publishing Company: https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA006/English/APC1928/GA006_index.html;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1910 | 1961) Das Christentum als mystische Tatsache und die Mysterien des Altertums, translated as Christianity as Mystical Fact, by E. A. Frommer, Gabrielle Hess and Peter Kändler, by Rudolf Steiner Publications, Inc.: https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA008/English/RPC1961/GA008_index.html;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1923 | 1973) Die Rätsel der Philosophie, translated as Riddles of Philosophy, by Fritz C. A. Koelln, Anthroposophic Press, Spring Valley, New York, GA 018: https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA018/English/AP1973/GA018_index.html.

14. Much has been written about the birth of modern science in the Renaissance. This chapter leads us on the journey towards that event, via;

– The atoms of Democritus and how they were rediscovered by way of the epicurean poem De Rerum Naturae in the 15th century;

– Nominalism and Medieval scholastic philosophy and the birth of empirical and rational science – the death of (strong, metaphysical) realism and the birth of the detached scientist.

Some useful quotes from Wikipedia, Primary–secondary quality distinction:

- “By convention there are sweet and bitter, hot and cold, by convention there is colour; but in truth there are atoms and the void”

—Democritus, Fragment 9.

- “I think that tastes, odours, colours, and so on are no more than mere names so far as the object in which we locate them are concerned, and that they reside only in the consciousness. Hence if the living creature were removed, all these qualities would be wiped away and annihilated”

—Galileo Galilei, The Assayer (published 1623).

- “[I]t must certainly be concluded regarding those things which, in external objects, we call by the names of light, colour, odour, taste, sound, heat, cold, and of other tactile qualities, […]; that we are not aware of their being anything other than various arrangements of the size, figure, and motions of the parts of these objects which make it possible for our nerves to move in various ways, and to excite in our soul all the various feelings which they produce there.”

—René Descartes, Principles of Philosophy (published 1644/1647).

- “For the rays, to speak properly, are not coloured. In them there is nothing else than a certain power and disposition to stir up a sensation of this or that colour.”

—Isaac Newton, Optics (3rd ed. 1721, original in 1704).

References include:

- Bortoft, Henri (1996) The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe’s Way Toward a Science of Conscious Participation in Nature, Lindisfarne Books;

- Dijksterhuis, Eduard Jan (1969) The Mechanization of the World Picture, Oxford University Press;

- Edelglass, Stephen; Maier, Georg; Gebert, Hans & Davy, John M. (1996) Matter and Mind: Imaginative Participation in Science, Floris Books;

- Francis, Keith (2012) Steiner and the Atom, Adonis Press;

- Holmyard, Eric John (1931) Makers of Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press: https://archive.org/details/makersofchemistr029725mbp/;

- Hubert, Christian (2019) Clinamen, Christian Hubert Studio: https://www.christianhubert.com/writing/clinamen;

- Lehrs, Ernst (1985) Man or Matter, Rudolf Steiner Press;

- Leyf Treinen, Max (2020) The Redemption of Thinking: A Study in Truth, Knowledge, and the Evolution of Consciousness with Special Reference to Johann Von Goethe, Owen Barfield, and Rudolf Steiner, Amazon Digital Services, Kindle edition;

- Luria, S. Y. (1970) Democritus: Texts, Translation, Investigations, Translated by Taylor, C. C. W.: https://www.academia.edu/25014428/S.Y_Luria_Demokrit_English_translation_by_C.C.W_Taylor;

- Midgley, Mary (2006) Science and Poetry, Routledge Classics.

- Nicholl, Charles (2011) The Swerve: How the Renaissance Began by Stephen Greenblatt – review, The Observer: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/sep/23/the-swerve-stephen-greenblatt-review;

- Serres, Michel (2017) Extract from The Birth of Physics by Michel Serres, translated by David Webb, with an introduction by Bill Ross, Parrhesia 27, 1-12: https://parrhesiajournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/parrhesia27_serres.pdf;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1914 | 1961) Human and Cosmic Thought (Der menschliche und der kosmische Gedanke), GA 151: https://rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA151/English/RSP1961/19140121p01.html;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1923 | ?) Realism and Nominalism (Ursprung des heutigen Geisteslebens aus der Scholastik), lecture 11 of 12 from the lecture series A Living Knowledge of Nature, the Fall of the Intellect into Sin, the Spiritual Resurrection, 27 January 1923, Dornach, GA 220: https://rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA220/English/Singles/19230127p01.html;

- Wikipedia contributors (2024) Primary–secondary quality distinction, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primary%E2%80%93secondary_quality_distinction;

- Wikipedia contributors (2024) Scientific Revolution, Wikipedia :https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_Revolution.

15. Despite the growing current of nominalism and rationalism, the mysteries of life and of chemical substance were still largely the province of alchemy, despite the disapproval of the church. Many pursued alchemy in the hopes of material gold and eternal life and were ridiculed for either being charlatans or dilettantes. However others such as Basil Valentine, Agrippa of Nettesheim, Raymond of Sabunda and Paracelsus maintained a belief and understanding of ancient holistic, spiritual knowledge, including that of Pythagoras and Aristotle, as well as from even more ancient mystical sources.

Some of the key themes in Renaissance alchemy are referenced in this picture below;

Heinrich Khunrath’s Amphitheatrum sapientiae aeternae, Hamburg: s.n., 1595. Click on the image for the full resolution original.

“Khunrath depicts the alchemist in a metaphorical laboratory divided into an altar to the labour of alchemical practice and one to the Divine Word. The table of musical instruments bridges the alembics of the laboratory furnace and the books of divine revelation. The instruments are emblematic of the mathematical harmonies underpinning the natural order of the universe.” Quote from https://www.princeton.edu/~his291/Alchemy_1.html relating to the 1609 engraving of an idealised alchemist’s laboratory by Heinrich Khunrath, a theosophist, cabalist, and Hermetic mystic. An enlarged view of the altar on the left shows a book displaying a pentagram, probably a reference to the sacred mathematics of Pythagoras and the harmony of the spheres.

This chapter needs to be a link between older alchemy and related mystery knowledge and the Ideas of Goethe and Rudolf Steiner. For example, the concepts of unity; duality and polarity; threefold-ness of the human being, the tria principia; fourfold human being, kingdoms of nature, elements, ethers; seven classical planets, days, trees, metals, life processes, worldviews; twelve months, senses, moods, virtues, zodiac signs.

Sir Isaac Newton has generally been considered to have been a rationalist, mechanical philosopher, however, when his personal papers and library became publicly available he was described, thus;

Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians…

– John Maynard Keynes, “Newton, the Man”, cited by https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Newton.

For example, he considered that of the cures for the plague,

the best is a toad suspended by the legs in a chimney for three days, which at last vomited up earth with various insects in it, on to a dish of yellow wax, and shortly after died. Combining powdered toad with the excretions and serum made into lozenges and worn about the affected area drove away the contagion and drew out the poison.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/jun/02/isaac-newton-plague-cure-toad-vomit.

It is easy for us to laugh at such remedies today, however to do so is to ignore the Ideas that lay behind them.

My references currently include:

- Anthrowiki contributors (2024) The Three Logoi: https://en.anthro.wiki/Logos#The_Three_Logoi;

- Anthrowiki contributors (2024) Tria principia: https://en.anthro.wiki/Tria_principia;

- Bortoft, Henri (1996) The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe’s Way Toward a Science of Conscious Participation in Nature, Steiner Books;

- Dijksterhuis, Eduard Jan (1969) The Mechanization of the World Picture, Oxford University Press;

- Gray, Ronald Douglas (1952 | 2010) Goethe The Alchemist, Cambridge University Press;

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. (2013) Western Esotericism: A Guide for the Perplexed, Bloomsbury Academic;

- Hauck, Dennis William (2008) The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Alchemy: The Magic and Mystery of the Ancient Craft Revealed for Today, ALPHA BOOKS, Published by Penguin Random House LLC;

- Hauschka, Rudolf (2002) The Nature of Substance: Spirit and Matter, Rudolf Steiner Press;

- Holmyard, Eric John (1931) Makers of Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press. https://archive.org/details/makersofchemistr029725mbp/;

- Kuhnrath, Heinrich (1609) Tractatus III, sen Basilica Philosophica, From Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tractatus_III,_sen_Basilica_Philosophica_Wellcome_M0012392.jpg;

- Lehrs, Ernst (1985) Man or Matter, Rudolf Steiner Press;

- Luria, S. Y. (1970) Democritus: Texts, Translation, Investigations, Translated by Taylor, C. C. W.: https://www.academia.edu/25014428/S.Y_Luria_Demokrit_English_translation_by_C.C.W_Taylor;

- Princeton University History 291 (2024) The Scientific Revolution and European Order, 1500-1750: https://www.princeton.edu/~his291/;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1910 | 1961) Das Christentum als mystische Tatsache und die Mysterien des Altertums, translated as Christianity as Mystical Fact, by E. A. Frommer, Gabrielle Hess and Peter Kändler, by Rudolf Steiner Publications, Inc.: https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA008/English/RPC1961/GA008_index.html;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1918 | 1947) Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?, translated as Knowledge of Higher Worlds and its Attainment, by George Metaxa, with revisions by Henry B. Monges, Anthroposophic Press, GA 010: https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA010/English/RSPC1947/index.html;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1922 | 1971) Theosophie: Einführung in übersinnliche Welterkenntnis und Menschenbestimmung, translated as Theosophy: An Introduction to the Supersensible Knowledge of the World and the Destination of Man, by Henry B. Monges and Gilbert Church, Anthroposophic Press, GA 009: https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA009/English/AP1971/GA009_index.html;

- Steiner, Rudolf (1925 | 1972) Die Geheimwissenschaft im Umriss, translated as An Outline of Occult Science, translated by Maud and Henry B. Monges, The Anthroposophic Press, GA 013: https://rsarchive.org/Books/GA013/English/AP1972/GA013_index.html.

16. Thony Christie is an exceedingly knowledgeable historian of Renaissance science who writes on the Internet at https://thonyc.wordpress.com/. Hopefully with his guidance I am less likely to make some of the errors that many before me have made, perpetuating myths about the relationships between astronomy, astrology, physics, chemistry, alchemy and mathematics.

Reading includes;

- Bortoft, Henri (1996) The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe’s Way Toward a Science of Conscious Participation in Nature, Steiner Books;

- Browne, Charles A. (1944) A Source Book of Agricultural Chemistry, The Chronica Botanica Co;

- Christie, Thony (2024) The Renaissance Mathematicus: https://thonyc.wordpress.com/;

- Dijksterhuis, Eduard Jan (1969) The Mechanization of the World Picture, Oxford University Press;

- Edelglass, Stephen; Maier, Georg; Gebert, Hans & Davy, John M. (1996) Matter and Mind: Imaginative Participation in Science, Floris Books;

- Francis, Keith (2012) Steiner and the Atom, Adonis Press;

- Lehrs, Ernst (1985) Man or Matter, Rudolf Steiner Press;

- Midgley, Mary (2006) Science and Poetry, Routledge Classics;

- Nicholl, Charles (2011) The Swerve: How the Renaissance Began by Stephen Greenblatt – review, The Observer: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/sep/23/the-swerve-stephen-greenblatt-review;

- Serres, Michel (2017) Extract from The Birth of Physics by Michel Serres, translated by David Webb, with an introduction by Bill Ross, Parrhesia 27, 1-12: https://parrhesiajournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/parrhesia27_serres.pdf;

- Wikipedia contributors (2024) Scientific Revolution, Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_Revolution.

17. References include;

- Bohning, James J.; Bret, Patrice; and Demeulenaere-Douyère, Christiane (1999) The Chemical Revolution of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, International Historic Chemical Landmark at the Académie des Sciences in Paris 1999, American Chemical Society: http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/lavoisier.html

- Boyle, Robert (1661) The Sceptical Chymist, Edgar Fahs Smith Memorial Collection (University of Pennsylvania): https://colenda.library.upenn.edu/catalog/81431-p3zw1983s;

- Browne, Charles A. (1944) A Source Book of Agricultural Chemistry, The Chronica Botanica Co;

- Christie, Thony (2024) The Renaissance Mathematicus: https://thonyc.wordpress.com/;

- Dijksterhuis, Eduard Jan (1969) The Mechanization of the World Picture, Oxford University Press;

- Holmyard, Eric John (1931) Makers of Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press: https://archive.org/details/makersofchemistr029725mbp/;

- Lehrs, Ernst (1985) Man or Matter, Rudolf Steiner Press;

18. The nineteenth century represented a major turning point in human history, including science, technology, philosophy, art and culture. As far as science and philosophy was concerned the so-called atom was at the centre of much of that change.

Of particular concern for the composition of this book are those properties of solids, liquids and gasses which Nick Thomas (in chapters 19 and 20) explained without the need of an atomic conception. Those aspects relating to thermodynamics (heat and energy) are covered in chapter 14.

References include;

- Bohning, James J.; Bret, Patrice; and Demeulenaere-Douyère, Christiane (1999) The Chemical Revolution of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, International Historic Chemical Landmark at the Académie des Sciences in Paris 1999, American Chemical Society: http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/lavoisier.html;

- Browne, Charles A. (1944) A Source Book of Agricultural Chemistry, The Chronica Botanica Co;

- Francis, Keith (2012) Steiner and the Atom, Adonis Press;

- Hauschka, Rudolf (1950 | 2002) The Nature of Substance: Spirit and Matter, Rudolf Steiner Press: https://archive.org/details/TheNatureOfSubstanceRudolfHauschka/;

- Holleman, L.W.J. (1982 | 1999) A Review of Research on the Biological Transmutation of Chemical Elements: Based on an unfinished paper by Prof. L.W.J. Holleman, translated and completed with criticism by David Cuthbertson: http://www.holleman.ch/holleman.html;

- Holmyard, Eric John (1931) Makers of Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press: https://archive.org/details/makersofchemistr029725mbp/;

- Lehrs, Ernst (1985) Man or Matter, Rudolf Steiner Press;

- Morrisson, Mark (2007) Modern Alchemy Occultism and the Emergence of Atomic Theory, Oxford University Press;

- Thomas, Nick (1999) Science Between Space and Counterspace: Exploring the Significance of Negative Space, Temple Lodge Publications;

- Unger, Georg (1978 | 1982/3) On Nuclear Energy and the Occult Atom (English translation of ‘Von Wesen der Kernergie’), The Anthroposophic Press, Spring Valley, New York.

19. See Baumgartner (1992), Hauschka (1950), Holleman (1982 | 1999) and Preuss (1899).

20. See Biberian (2012), Freundler (1928), Holleman (1982 | 1999), Kervran (1998), Pictet (1925).

21. See Biberian (2022), Holleman (1982 | 1999). This for me is the easiest chapter to write since I was responsible for writing and interpreting both of their transmutation experiments. It should therefore be the first to be written.

22. See Vysotskii and Kornilova (2010). The quantum electro-dynamics that Vysotskii uses to provide a mathematical model of the biological transmutation phenomenon needs to be explained in the following two chapters. Chapters 9, 10 & 12 should be the next to be written.

23. See Lehrs (1985); Action at a distance – Wikipedia; History of electromagnetic theory – Wikipedia; Francis (2012) Steiner and the Atom; and Thomas, Nick (1999).

The final details of these two chapters (13 and 14) has not been decided. They are required to communicate the nature of the tamed materialistic lion – of nuclear physics. They are also required to communicate something of the extraordinary mysteries of light, time, distance, gravitational mass and the geometry of space. These were most famously mathematically modelled by the genius of Einstein who in 1905 wrote four ground-breaking papers related to two extremes of scale – the exceedingly small (quantum mechanics) and the exceedingly large (relativity). The mathematics and in particular the non-Euclidean geometrical concepts of higher dimensions that were required to develop these ideas were largely being developed during Rudolf Steiner’s time as a student. Their use in developing new concepts that transcended the classical physics of Isaac Newton happened largely in the last 25 years of Steiner’s life.

The other determinant of what goes in which chapter is Nick Thomas’s Science Between Space and Counterspace. His work also depend on the earlier chapters of the final part of the book. I therefore propose writing the book out of order. The final part of the book is to be written before the last half of this book.

24. See previous chapter and footnote 23 above.

25. The final seven chapters should be written after chapters 9-12. However, I am looking to develop a language to express the linked material and Ideal realms which only together form the reality we experience. It is a language which needs to be capable of expressing the holistic nature of reality and which builds bridges between the many different schools of academic thought as well as that of Rudolf Steiner’s spiritual science. Therefore, before writing this final part of the book I need to start with where most of our technical words have originated and which were later developed to help form our subsequent ideas through history, starting with the Ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle.

For references, see Bortoft (1996); Caisley (2022); Chad (2010); Goethe (1792 | 2010); Gray ([1952] 2010); Lehrs (1985); Leyf Treinen (2020); Miller (1988); Steiner ([1883-1897] 1988); Steiner ([1897] 1928); Steiner ([1918c] 1985); Talbott (1998); Wise (2016); Ziguras (2011).

26. For references see Bartelme (2017); Heusser (2016); Lehrs (1985); Leyf Treinen (2020); Numerous books by Steiner including; (1892) Truth and Science; (1894) The Philosophy Of Freedom; (1902) Christianity As Mystical Fact; (1904) Theosophy; (1904) How To Know Higher Worlds; (1910) Occult Science; (1914) Human and Cosmic Thought; (1925) My Autobiography; Tazer-Myers (2019); Unger ([1978] 1982/3); Wilkinson (1993);

The Science Group of the Anthroposophical Society in Great Britain has an excellent reading list: https://sciencegroup.org.uk/2021/11/09/bibliography/.

27. He wrote a number books and articles which followed Steiner’s mathematical and scientific indications, often with the support of his assistant and co-worker Olive Whicher;

- Adams, George (1933) Space and the Light of the Creation; A new Essay in Cosmic Theory, London;

- Adams, George (1965) Physical and Ethereal Spaces, London;

- Adams, George (1977) Universal Forces in Mechanics, London;

- Adams, George (1978) A Letter from George Adams, Rudolf Steiner Press;

- Adams, George, Whicher, Olive (1949) The Living Plant and the Science of Physical and Ethereal Spaces: A Study of the Metamorphosis of Plants in the Light of Modern Geometry and Morphology, Goethean Science Foundation;

- Adams, George, Whicher, Olive (1980) The Plant Between Sun and Earth, Rudolf Steiner Press;

- Whicher, Olive (1964) The Life and Work of George Adams: an Introduction, Golden Blade 16: 27-53;

- Whicher, Olive (1971) Projective Geometry – Creative Polarities in Space and Time, Rudolf Steiner Press;

- Whicher, Olive (1975) The Idea of Counterspace, Steiner Books;

- Whicher, Olive (1989) Sun Space: Science at a Threshold of Spiritual Understanding, Rudolf Steiner Press;

- Whicher, Olive (1997 | 2015) The Heart of the Matter: Discovering the Laws of Living Organisms, Temple Lodge Publishing.

28. For Olive Whicher see some of the above. For a wider consideration of etheric, astral and ego forces see;

- Atkinson, Glen (2020) The Problem of the Etheric Formative Forces, Glenopathy, Secular Energetic Biodynamic Agriculture: https://garudabd.org/wp-content/uploads/EFF-v6-1.pdf;

- Bartelme, Ricardo R. (2017) Anthroposophic Medicine, an Introduction; and a Book Review of Anthroposophy and Science, Integrative Medicine (Encinitas). 2017 Aug; 16(4): 42–46: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6415628/;

- Bietkowski, P., Grześ, S. (2024) Reflective sketches: the biodynamic impulse (Dr Rudolf Steiner) in Central Europe, J. Agribus. Rural Dev., 1(71), 125–134: http://dx.doi.org/10.17306/J.JARD.2024.01838;

- Hauschka, Rudolf (1950 | 2002) The Nature of Substance: Spirit and Matter, Rudolf Steiner Press: https://archive.org/details/TheNatureOfSubstanceRudolfHauschka/;

- Heusser, Peter (2016) Anthroposophy and Science: An Introduction, Peter Lang (publ.);

- Lehrs, Ernst (1985) Man or Matter, Rudolf Steiner Press;

- Pfeiffer, Ehrenfried (2013) Preface, to Steiner, Rudolf ([1924] 2013) Agriculture Course: The Birth of the Biodynamic Method, translated by George Adams, Rudolf Steiner Press: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=liFFDwAAQBAJ.

29. The work of Nick Thomas was for me was of the utmost importance. It provided a way of independently testing many of the strange scientific indications of Rudolf Steiner. Two such indications were that the sun consists of negative space and that light does not travel at a fixed speed (in a vacuum) but instantaneously fills a space. These superficially strange ideas for anyone trained or well read in mainstream academic physics were shown by Thomas to be the natural consequence of a linked space – counterspace Idea of nature, which I wish to call physis. Thomas created a geometrised version of the hylomorphic concept which Aristotle wrote about in his Physike Akroasis, which though normally translated as Physics, literally means Of the Hearing of Things Natural, or Lectures on Nature. This was also Goethe’s conception of nature, hence Adams provisionally naming an early account of his work Goethean mathematical physics.

Of these two chapters, this, the first introduces the basic principles – the geometrical spaces which Thomas found to be most appropriate with which to mathematically describe the behaviours of materials, each with the qualities of earth (solid), or water (liquid), or air (gas). Fire was found to be something special – in a category of its own. Each of these variants or states of physical matter was linked to their prospective dual geometrical opposite for each three of their equivalent ethers – light with air, chemical with water and life with earth. As a result he was able to show that the force of gravity on solid objects was due to its linkage with etheric space. This explains the spooky action-at-a-distance nature of this force. The material aspect of this point-centred force is therefore density, which may be contrasted with the etheric plane centred, suctional force generally characterised as levity – the force which enabled Newton’s famous apple to reach the top of the tree.

30. This second chapter relating to Thomas’s work looks at the consequences of a new understanding of what was explored in the last two chapters (13 and 14) of the second part of this book.

For reference, Nick Thomas wrote a number of essays and books on this and related subjects:

- Thomas, Nick (1996) Rethinking Physics, Science Group of the Anthroposophical Society in Great Britain, Newsletter articles Supplement (now called Archetype), pp 1-11.

- Thomas, Nick (1999) Science Between Space and Counterspace: Exploring the Significance of Negative Space, Temple Lodge Publications.

- Thomas, Nick (2008) Space and Counterspace: A New Science of Gravity, Time and Light, Floris Books.

His essays which have been collected on the Internet from a variety of unknown sources are. If anyone can give me any further information about these, or of any that I have missed, I would like to hear from you:

- Anthroposophy and the Four Ethers;

- Counterspace and Organisms, Science Group of the Anthroposophical Society in Great Britain Newsletter – September 1999;

- CHAOS, LIFE and FREEWILL;

- Counterspace Research;

- Elliptic Congruences and Astronomy;

- Exploring Negative Space;

- Approaching Freedom Through Love;

- Matter is Woven Light;

- A SHORT [Auto]BIOGRAPHY;

- Path Curves;

- Phenomenalism and Counterspace;

- PHYSICALISM;

- PIVOT TRANSFORMS;

- SCIENCE AND INWARDNESS;

- The Emanations of the Hierarchies;

- THE FOUR ETHERS;

- The Future is Now, Anthroposophy at the New Millenium;

- AN APPROACH TO THE LEMNISCATE PATH OF THE SUN AND EARTH;

- The Molten Sea and Initiation;

- THE SUN;

- Tuning Thinking to Reality;