The Beginnings of Chemistry and the Ending of Realism

| This text is in a coloured box to separate it from the rest of the chapter. It is a comment about this working draft chapter. The text below started as a more or less conventional historical review of the early developments of chemistry in the West. The first parts of the Wikipedia page, History of Chemistry, was used as a template for this early draft. This update interweaves its content with Rudolf Steiner’s Riddles of Philosophy. Also used is E.J. Dijksterhuis The Mechanization of the World Picture. |

The mysteries to be explored in this book largely fall under the subject matter of chemistry. Though I was not particularly talented at school or university in the practical art of chemistry, I have always been fascinated by its apparent magical qualities. There is something deeply mysterious about it. I remember as a child seeing a painting of an alchemist’s laboratory and wishing that I might possess such a wondrous room.

Nevertheless, the history of chemistry is effectively the story of the progressive loss of its magic, which was systematically replaced by clear mathematical thinking. I recall reading (somewhere!) that Rudolf Steiner said this was a very necessary historical development. Part of my homework for this chapter is to find, read and understand just exactly what Steiner did say…

Early Humanity

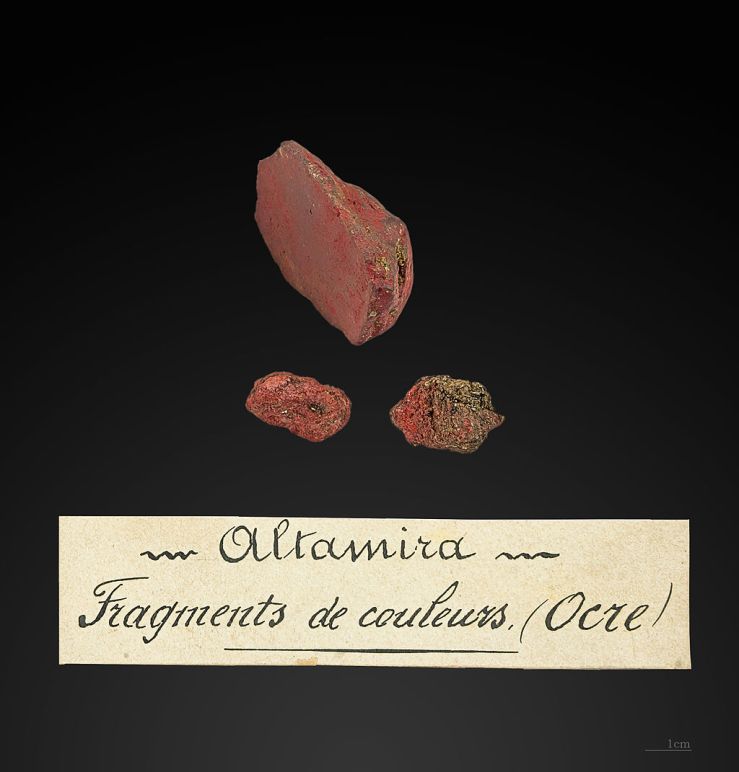

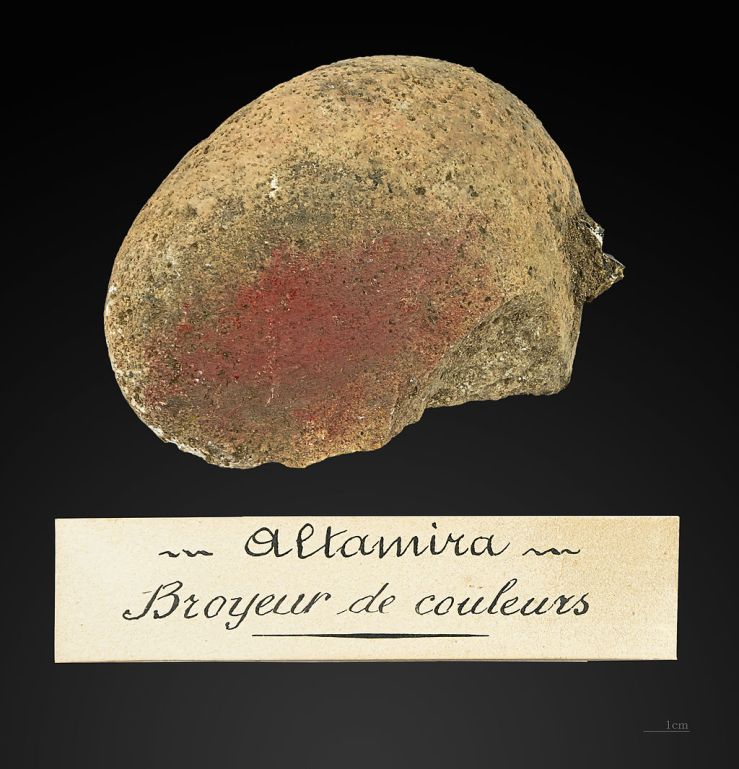

The earliest known working with chemical substances involved the grinding and mixing into a paste of the naturally occurring red and yellow ochres to produce paint. The ground mineral taken from the earth was mixed from a fluid to make a paste which could be applied to their own bodies, skins, and in a form which still survives today, the many prehistoric paintings which adorn certain caves on every continent on Earth. By means of an inanimate mineral substance, mixed with a fluid substance, the souls of the animals which they hunted could be re-created in paint.

Fire

Fire was another of our prehistoric legacies. Bushfires are naturally started by lightning. Great energetic rips in the fabric of our reality; enabling the appearance of red tongues of tremendous heat and light, which feast on organic matter, transforming it into smoke, charcoal and ashes. The fire could be collected, nurtured, and maintained as a sacred entity. Later, through the striking of certain rocks – flint against nodules of marcasite (iron ore) or meteoric iron – sparks could be formed – like miniature orange stars. These, when carefully captured and nurtured using fine dry kindling and with the action of the breath or wind, these sparks can generate a red hot glowing ember. At first the ember merely increases in intensity, then as the kindling heats up it will emit increasing amounts of acrid smoke. And then – with a sudden burst of heat, light and sound – the mass of kindling erupts into ever hungry burning flames.

The transformative powers of fire are truly magical. From wood comes heat and light. Water can become gas (or vapour). Food when roasted will change its colour, texture and taste. Earth – in the form of stone or soil – can change colour. Clay can be baked hard as stone. Some rocks can even be transformed into liquid, which – on cooling – form new glassy, or even metallic substances. Stones can also hold heat, and when dropped into water holding vessels, can cause the water to boil without the vessel being damaged by the fire. Knowledge of the transformative powers of fire would have been highly prized. In the wrong hands it is deadly. In the right hands it can nurture life. It might be considered as a portal between realms.

Early Metallurgy

The earliest metals to be valued by humanity – collected and shaped for ornament, symbolism, or utility – were those which occur naturally in their native form. Gold is the earliest known and most obvious example. Its colour, lustre, weight and malleability are truly remarkable.

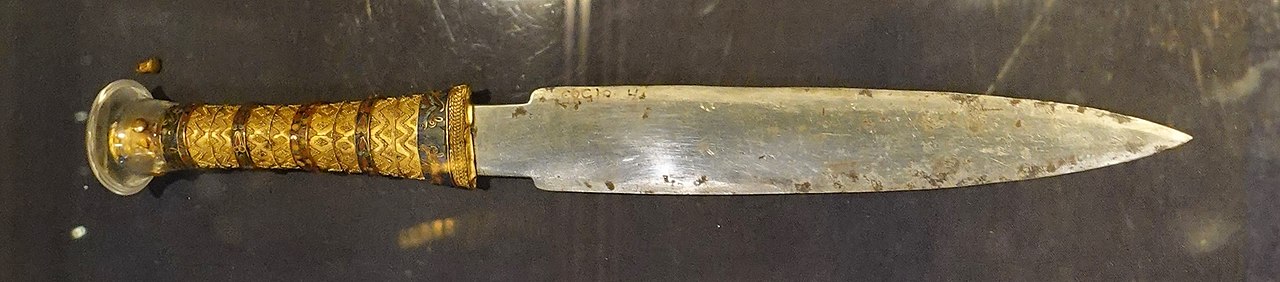

Iron from the sky was certainly known in at least Ancient Egyptian times. It would have been a rare and memorable event indeed to have witnessed a flaming meteorite fall from the heavens. Though much less malleable than gold, such iron rich meteorites would have been exceedingly precious gifts from the heavens indeed. A blade hammered out from such a stone would reflect the light in a similar manner to gold, but unlike gold it could cut and keep its edge. In English, in winter, when the earth is frozen solid, it is said to be as hard as iron.

Silver, copper and tin may also be found as naturally occurring metallic nuggets, which – due to their metallic, malleable nature – can also be worked into beautiful, precious objects. The secrets of their sacred magick (as opposed to the magic of tricksters and conjurers) which they possessed or enabled would have been strongly guarded.

Bronze Age

Certain metals can be recovered from their ores by simply heating the rocks in a fire: notably tin, lead and (at a higher temperature) copper. This process is known as smelting. Rocks containing veins of green coloured copper ore can be hammered into small fragments, and these can be smelted in clay vessels or furnaces. High temperatures are required. This required furnace technology to be developed, to enable extra air to be forced into the charcoal fire using some form of bellows. It seems that each cultural region developed its own unique methods for producing pure molten copper. This indicates that the methods were closely guarded secrets, passed on only to trusted initiates. The molten copper can be either poured into a shaped mould, or into a single ingot to be hammered into shape and worked into beautiful, treasured objects.

In time, it would have been observed that certain impurities which may be present with the copper, such as arsenic or (more rarely) tin, both lowered the melting point of the copper, increased its fluidity (easier to pour into intricate moulds) and increased the hardness of the final object. Through careful observation and experimentation tin – as a separately mined ore – was purposely added to the copper to produce what we now know as bronze.

Iron Age

Whilst the principles learnt from smelting bronze could be applied to that of the commonly available iron ore, the considerably higher melting point of iron made it a significantly more challenging task. The development of new sophisticated technologies were required. The superior properties of iron tools made the extra effort worth while.

Classical Antiquity and Atomism

Technological innovations may have been developed by this time, but their conception was not seen as we do today. They were not created or understood by means of abstract thought, but through imaginative (creative but exact) thought pictures [Riddles of Philosophy, Rudolf Steiner]. However, after the time of Homer, humankind began to feel separate from the world of Gods and elemental beings. As Steiner said: “Their thought pictures developed as a tool of truth“.

Some consider the first Greek philosopher to have been Pherecydes. In his world conception everything was constituted through the actions of three Ideas (divine beings). Only fragments survive of his text. Rudolf Steiner interpreted his ideas in Riddles of Philosophy.

Chronos was time – but not in the modern sense of measured clock time. Chronos was a being with the qualities or essence of time; it devours Chthon, a being with the qualities of earth, of the solid element. “Chronos lives in the activity of fire or warmth.” Again, this is not actual fire – as it is sensually experienced – it is the consuming activity of fire, of warmth, which is Chronos.

Zeus (or Zas), Steiner associated with the dissolving of water – from liquid to vapour, and of clouds of vapour when they dissolve into the air – the action of spatially spreading or even the force of centrifugal extension (the etheric force as conceived of by Steiner).

Chthon (Chthonie) – Pherecydes’ third being – Steiner wrote that it was seen in the action of water becoming solid, or solid becoming fluid.

These three beings may seen as interdependent. It is only through Zeus that Chronos consumes Chthon.

In the view of Pherekydes the world is constituted through the cooperation of these three principles. Through the combination of their action the material world of sense perception — fire, air, water and earth — come into being on the one hand, and on the other, a certain number of invisible supersensible spirit beings who animate the four material worlds. Zeus, Chronos and Chthon could be referred to as “spirit, soul and matter,” but their significance is only approximated by these terms. It is only through the fusion of these three original beings that the more material realms of the world of fire, air, water and earth, and the more soul-like and spirit-like (supersensible) beings come into existence. Using expressions of later world conceptions, one can call Zeus, space-ether; Chronos, time-creator; Chthon, matter-producer — the three “mothers of the world’s origin.” We can still catch a glimpse of them in Goethe’s Faust, in the scene of the second part where Faust sets out on his journey to the “mothers.”

Rudolf Steiner, Riddles of Philosophy.

Thales most famously stated that the fundamental origin and being of all things was to be found in “water”. He was a contemporary of Pherecydes, and he founded the Milesian school, which introduced a conception of nature in terms of observable entities.

Anaximander most famously stated that the fundamental origin and being of all things was to be found in the “infinite” (apeiron). He was taught by Thales and became the second master of the Milesian school.

Anaximenes stated that the fundamental and origin and being of all things was to be found in “air”. He was either a younger friend or student of Anaximander at the Milesian school, and was the last of the reknown Milesian philosophers.

Heraclitus stated that the fundamental and origin and being of all things was to be found in “fire”. Like Thales, Anaximander and Anaximenes before him, he was from the Ionian school (of which the Melesian school had been a part). They were collectively called the physiologoi (those who discoursed on nature) by Aristotle.

What is not considered in this treatment is the fact that these men are still really living in the process of the genesis of intellectual world conception. To be sure, they feel the independence of the human soul in a higher degree than Pherekydes, but they have not yet completed the strict separation of the life of the soul from the process of nature. One will, for instance, most certainly construct an erroneous picture of Thales’s way of thinking if it is imagined that he, as a merchant, mathematician and astronomer, thought about natural events and then, in an imperfect yet similar way to that of a modern scientist, had summed up his results in the sentence, “Everything originates from water.” To be a mathematician or an astronomer, etc., in those ancient times meant to deal in a practical way with the things of these professions, much in the way a craftsman makes use of technical skills rather than intellectual and scientific knowledge.

What must be presumed for a man like Thales is that he still experienced the external processes of nature as similar to inner soul processes. What presented itself to him like a natural event, as did the process and nature of “water” (the fluid, mudlike, earth-formative element), he experienced in a way that was similar to what he felt within himself in soul and body. He then experienced in himself and outside in nature the effect of water, although to a lesser degree than man of earlier times did. Both effects were for him the manifestation of one power. It may be pointed out that at a still later age the external effects in nature were thought of as being akin to the inner processes in a way that did not provide for a “soul” in the present sense as distinct from the body. Even in the time of intellectual world conception, the idea of the temperaments still preserves this point of view as a reminiscence of earlier times.

One called the melancholic temperament, the earthy; the phlegmatic, the watery; the sanguinic, the airy; the choleric, the fiery. [Wikipedia provides a general introduction to the four temperaments.] These are not merely allegorical expressions. One did not feel a completely separated soul element, but experienced in oneself a soul-body entity as a unity. In this unity was felt the stream of forces that go, for instance, through a phlegmatic soul, to be like the forces in external nature that are experienced in the effects of water. One saw these external water effects to be the same as what the soul experienced in a phlegmatic mood. The thought habits of today must attempt an empathy with the old modes of conception if they want to penetrate into the soul life of earlier times.

In this way one will find in the world conception of Thales an expression of what his soul life, which was akin to the phlegmatic temperament, caused him to experience inwardly. He experienced in himself what appeared to him to be the world mystery of water. The allusion to the phlegmatic temperament of a person is likely to be associated with a derogatory meaning of the term. Justified as this may be in many cases, it is nevertheless also true that the phlegmatic temperament, when it is combined with an energetic, objective imagination, makes a sage out of a man because of its calmness, collectedness and freedom from passion. Such a disposition in Thales probably caused him to be celebrated by the Greeks as one of their wise men.

For Anaximenes, the world picture formed itself in another way. He experienced in himself the sanguine temperament. A word of his has been handed down to us that immediately shows how he felt the air element as an expression of the world mystery. “As our soul, which is a breath, holds us together, so air and breath envelop the universe.”

The world conception of Heraclitus will, in an unbiased contemplation, be felt directly as a manifestation of his choleric inner life. A member of one of the most noble families of Ephesus, he became a violent antagonist of the democratic party because he had arrived at certain views, the truth of which was apparent to him in his immediate inner experience. The views of those around him, compared with his own, seemed to him to prove directly in a most natural way, the foolishness of his environment. Thus, he got into such conflicts that he left his native city and led a solitary life at the Temple of Artemis. Consider these few of his sayings that have come down to us. “It would be good if the Ephesians hanged themselves as soon as they grew up and surrendered their city to those under age.” Or the one about men, “Fools in their lack of understanding, even if they hear the truth, are like the deaf: of them does the saying bear witness that they are absent when present.”

The feeling that is expressed in such a choleric temperament finds itself akin to the consuming activity of fire. It does not live in the restful calm of “being.” It feels itself as one with eternal “becoming.” Such a soul feels stationary existence to be an absurdity. “Everything flows,” is, therefore, a famous saying of Heraclitus. It is only apparently so if somewhere an unchanging being seems to be given. We are lending expression to a feeling of Heraclitus if we say, “The rock seems to represent an absolute unchanging state of being, but this is only appearance; it is inwardly in the wildest commotion; all its parts act upon one another.” The mode of thinking of Heraclitus is usually characterised by his saying, “One cannot twice enter the same stream, for the second time the water is not the same.” A disciple of Heraclitus, Cratylus, goes still further by saying that one could not even enter the same stream once. Thus it is with all things. While we look at what is apparently unchanging, it has already turned into something else in the general stream of existence.

We do not consider a world conception in its full significance if we accept only its thought content. Its essential element lies in the mood it communicates to the soul, that is, in the vital force that grows out of it. One must realise how Heraclitus feels himself with his own soul in the stream of becoming. The world soul pulsates in his own human soul and communicates to it of its own life as long as the human soul knows itself as living in it. Out of such a feeling of union with the world soul, the thought originates in Heraclitus, “Whatever lives has death in itself through the stream of becoming that is running through everything, but death again has life in itself. Life and death are in our living and dying. Everything has everything else in itself; only thus can eternal becoming flow through everything.” “The ocean is the purest and impurest water, drinkable and wholesome to fishes, to men undrinkable and pernicious.” “Life and death are the same, waking and sleeping, young and old; the first changes into the second and again into the first.” “Good and evil are one.” “The straight path and the crooked… are one.”

Anaximander is freer from the inner life, more surrendered to the element of thought itself. He sees the origin of things in a kind of world ether, an indefinite formless basic entity that has no limits. Take the Zeus of Pherekydes, deprive him of every image content that he still possesses and you have the original principle of Anaximander: Zeus turned into thought. A personality appears in Anaximander in whom thought life is borne out of the mood of soul that still has, in the preceding thinkers, the colour of temperament. Such a personality feels united as a soul with the life of thought, and thereby is not so intimately interwoven with nature as the soul that does not yet experience thought as an independent element. It feels itself connected with a world order that lies above the events of nature. When Anaximander says that men lived first as fishes in the moist element and then developed through land animal forms, he means that the spirit germ, which man recognises through thinking as his true being, has gone through the other forms only as through preliminary stages, with the aim of giving itself eventually the shape that has been appropriate for him from the beginning.

Rudolf Steiner, Riddles of Philosophy.

Steiner then goes on to speak of their successors;

Xenophanes of Kolophon (born 570 B.C.); Parmenides (460 B.C., living as a teacher in Athens), younger and inwardly related to Xenophanes; Zenon of Elea (who reached his peak around 500 B.C.); Melissos of Samos (about 450 B.C.).

The thought element is already alive to such a degree in these thinkers that they demand a world conception in which the life of thought is fully satisfied; they recognise truth only in this form. How must the world ground be constituted so that it can be fully absorbed within thinking? This is their question.

Rudolf Steiner, Riddles of Philosophy.

However important their contribution to philosophy may have been – and it was significant – it is beyond this introduction to the origins of chemistry.

Steiner continues:

Whoever does not see how, in the progress of human development toward the stage of thought experience, real experiences — the picture experiences — came to an end with the beginning of this thought life, will not see the special quality of the Greek thinkers from the sixth to the fourth pre-Christian centuries in the light in which they must appear in this presentation. Thought formed a wall around the human soul, so to speak. The soul had formerly felt as if it were within the phenomena of nature. What it experienced in these natural phenomena, like the activities of its own body, presents itself to the soul in the form of images that appeared in vivid reality. Through the power of thought this entire panorama was now extinguished. Where previously images saturated in content prevailed, thought now expanded through the external world. The soul could experience itself in the surroundings of space and time only if it united itself with thought.

Ancient world

Around 420 BC, Empedocles stated that all matter is made up of four elemental substances: earth, fire, air and water. The early theory of atomism can be traced back to ancient Greece and ancient India.[14] Greek atomism dates back to the Greek philosopher Democritus, who declared that matter is composed of indivisible and indestructible particles called “atomos” around 380 BC. Leucippus also declared that atoms were the most indivisible part of matter. This coincided with a similar declaration by Indian philosopher Kanada in his Vaisheshika sutras around the same time period.[14] In much the same fashion he discussed the existence of gases. What Kanada declared by sutra, Democritus declared by philosophical musing. Both suffered from a lack of empirical data. Without scientific proof, the existence of atoms was easy to deny. Aristotle opposed the existence of atoms in 330 BC. Earlier, in 380 BC, a Greek text attributed to Polybus argued that the human body is composed of four humours. Around 300 BC, Epicurus postulated a universe of indestructible atoms in which man himself is responsible for achieving a balanced life.

With the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience, the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius[15] wrote De rerum natura (The Nature of Things)[16] in 50 BC. In the work, Lucretius presents the principles of atomism; the nature of the mind and soul; explanations of sensation and thought; the development of the world and its phenomena; and explains a variety of celestial and terrestrial phenomena.

Much of the early development of purification methods is described by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia. He tried to explain those methods, as well as making acute observations of the state of many minerals.

Medieval alchemy

See also: Minima naturalia, a medieval Aristotelian concept analogous to atomism

The elemental system used in medieval alchemy was developed primarily by the Persian–Arab alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān and was rooted in the classical elements of Greek tradition.[17] His system consisted of the four Aristotelian elements of air, earth, fire, and water in addition to two philosophical elements: sulphur, characterizing the principle of combustibility, “the stone which burns”; and mercury, characterizing the principle of metallic properties. They were seen by early alchemists as idealized expressions of irreducible components of the universe[18] and are of larger consideration[clarification needed] within philosophical alchemy.

The three metallic principles (sulphur to flammability or combustion, mercury to volatility and stability, and salt to solidity) became the tria prima of the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus. He reasoned that Aristotle’s four-element theory appeared in bodies as three principles. Paracelsus saw these principles as fundamental and justified them by recourse to the description of how wood burns in fire. Mercury included the cohesive principle, so that when it left the wood (in smoke) the wood fell apart. Smoke described the volatility (the mercurial principle), the heat-giving flames described flammability (sulphur), and the remnant ash described solidity (salt).[19]

The philosopher’s stone

Alchemy is defined by the Hermetic quest for the philosopher’s stone, the study of which is steeped in symbolic mysticism, and differs greatly from modern science. Alchemists toiled to make transformations on an esoteric (spiritual) and/or exoteric (practical) level.[20] It was the protoscientific, exoteric aspects of alchemy that contributed heavily to the evolution of chemistry in Greco-Roman Egypt, in the Islamic Golden Age, and then in Europe. Alchemy and chemistry share an interest in the composition and properties of matter, and until the 18th century they were not separate disciplines. The term chymistry has been used to describe the blend of alchemy and chemistry that existed before that time.[21]

The earliest Western alchemists, who lived in the first centuries of the common era, invented chemical apparatus. The bain-marie, or water bath, is named for Mary the Jewess. Her work also gives the first descriptions of the tribikos and kerotakis.[22] Cleopatra the Alchemist described furnaces and has been credited with the invention of the alembic.[23] Later, the experimental framework established by Jabir ibn Hayyan influenced alchemists as the discipline migrated through the Islamic world, then to Europe in the 12th century CE.

During the Renaissance, exoteric alchemy remained popular in the form of Paracelsian iatrochemistry, while spiritual alchemy flourished, realigned to its Platonic, Hermetic, and Gnostic roots. Consequently, the symbolic quest for the philosopher’s stone was not superseded by scientific advances, and was still the domain of respected scientists and doctors until the early 18th century. Early modern alchemists who are renowned for their scientific contributions include Jan Baptist van Helmont, Robert Boyle, and Isaac Newton.

Alchemy in the Islamic world

In the Islamic World, the Muslims were translating the works of the ancient Greeks and Egyptians into Arabic and were experimenting with scientific ideas.[24] The development of the modern scientific method was slow and arduous, but an early scientific method for chemistry began emerging among early Muslim chemists, beginning with the 9th-century chemist Jābir ibn Hayyān (known as “Geber” in Europe), who is sometimes regarded as “the father of chemistry”.[25][26][27][28] He introduced a systematic and experimental approach to scientific research based in the laboratory, in contrast to the ancient Greek and Egyptian alchemists whose works were largely allegorical and often unintelligible.[29] He also invented and named the alembic (al-anbiq), chemically analyzed many chemical substances, composed lapidaries, distinguished between alkalis and acids, and manufactured hundreds of drugs.[30] He also refined the theory of five classical elements into the theory of seven alchemical elements after identifying mercury and sulfur as chemical elements.[31][verification needed]

| The sections on alchemy require splitting into two; the early and late periods. Although this a history of the development of chemical ideas in Western Europe, Byzantine, Arabic and Muslim knowledge had an enormous influence on Western thought and knowledge during the later Middle Ages. Therefore those aspects of its history relating to this period will be included here, ready to be carried forward in the following chapter. |

Leave a comment