As Rudolf Steiner said, in 1924, in the fifth of his Biodynamic Agriculture lectures; “Are not they themselves [scientists] already speaking frankly of a transmutation of the elements? Observation of several elements has tamed the materialistic lion in this respect, if I may say so.”

Examples of this are detailed by Mark Morrisson in his Modern Alchemy, Occultism and the Emergence of Atomic Theory. Of particular relevance was the New York Times, page 3 newspaper headline of November 23, 1924:

Synthetic Gold Might Disrupt World – Commercial Use Would Mean Chaos Without Regulation in Finance, Economist Says

AT last, the philosopher’s stone! A German chemist, idling with a quartz lamp and electric rays and quicksilver vapor, has blundered upon the secret which gave color to medieval mysticism and alchemy, the formula which charlatans pretended to have, which kings and Popes sought, and which Governments made an excuse for debasing their currencies….

Nevertheless, the article had pointed out that it cost the German chemist, Miethe, about $2,000 for the electric current to manufacture the $300 worth of gold he thought he had produced. He later discovered that the gold in his mercury had been an impurity. But the point is that this claim – however far fetched – was taken seriously.

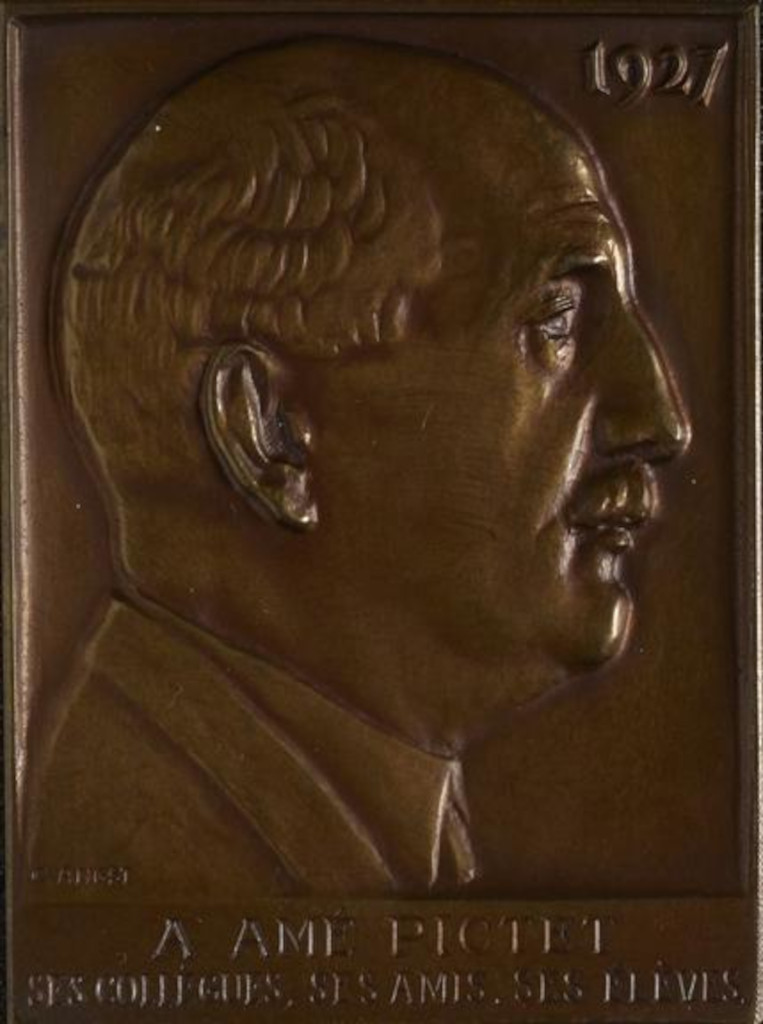

One of those investigating such matters was the Swiss chemist Amé Pictet. His student, Werner Scherrer, in collaboration with Louis Helfer were inspired by the observations of Louis Pasteur, who had found what they suspected were high levels of argon in yeast. Their results were published in Scherrer’s dissertation, La présence de l’argon dans les cellules vivantes, Helv. Chim. Acta 8, 537-545. The following is a rough translation of the introduction and the conclusions:

On the Presence of Argon in Living Cells

As soon as argon was discovered, it was hastily investigated if it existed elsewhere than in the atmosphere, and if, like the other elements of the air, it intervenes in the vital phenomena. In 1895 already, and at the instigation of Ramsay himself, G. Mac Donald and A. M. Kellas [Proc. Roy. Soc. London 57, 490 (1895)] examined from this point of view the gases released in the burning of peas; they found no argon there.

The following year, Kellas [Proc. Roy. Soc. London 59, 66 (1896)] arrived at a different result with regard to the gases of respiration; he found that the nitrogen withdrawn from the exhaled air contains a little more argon than that of the ambient air (1.210% by volume instead of 1.186).

After them, other researchers carried out similar research: G. Tolomei [C. 1897, I, 1030] recognised that the bacteria found on the pea roots fix not only nitrogen but also argon. Regnard and Schlösing [C. r. 124, 802 (1897)] determined the amount of argon contained in the blood gases: they found that one liter of horse blood contained 0.42 cm3 of argon. This quantity is twice as strong as the solubility of this gas in the blood serum should permit; that might suggest, argue these authors, that argon forms a loose combination with haemoglobin. This opinion, however, was immediately opposed by Zaleski [B. 30, 965 (1897)], who, having collected the gases from the combustion of haemoglobin, found no argon there.

We see that these first researches led to contradictory results. They were not, however, pursued. Once it was well established that argon is an inert gas, incapable of entering into any combination, the seeking of its presence in the tissues of living beings was renounced, and since 1898 the chemical literature has remained silent to this subject.

Inspired by some recent ideas on the relationship between vital phenomena and those of radioactivity, we thought it interesting to return to this question of the possible production of inert gases in biological processes.

Our first idea was to address, for this purpose, the gaseous products of the alcoholic fermentation of sugar. Pasteur has, indeed, remarked, since 1860 [Ann. chim. [3] 58, 323 (1860)], that the gases which are released during this fermentation are not entirely absorbed by potash; the carbon dioxide is mixed with a small amount of another gas. Pasteur seems to admit that this gas is nitrogen, but he does not give proof of it; and he adds, “These experiences deserve to be repeated.”

It will be seen in the following pages that, after having repeated Pasteur ‘s experiment, we have found that this foreign gas is for the most part nitrogen, but that it also contains a certain quantity of argon.

We then recognised that this argon pre-exists in yeast. In fact, if the dry yeast is burned in the presence of copper oxide, according to the method of Dumas for the determination of nitrogen, we see that this nitrogen contains a notable proportion of argon.

A similar combustion of the sheep brain, previously dried at 40° in the vacuum, also supplied us with argon.

Finally, after having coagulated the blood of beef, we subjected the clot to the same desiccation and to. the same combustion. The result was identical: 1 gr. clot releases about 1 cm3 of argon. Is this element in one of the constituents of the clot, fibrin or globules, in the state of a compound? We do not believe it, for, having repeated our test with pure fibrin and haemoglobin, we have no more than Zaleski, obtained the least trace of an inert gas.

The most likely explanation seems to be that argon is included in the gaseous state in yeast, brain and blood cells, and that escapes only when the walls of these cells come to be broken. As for its origin, it will be to new experiences to determine it. We will return to this point at the end of this article.

…

One last question remains to be answered: Is this argon of atmospheric origin and has it penetrated into the cells by a kind of assimilation, or does it come from some other source?

To this question we can not answer again; the solution of the problem will have to come from new experiences. But while waiting for these experiments to be made, we can not help but make an assumption, a simple working hypothesis, which, of course, we allow ourselves to present only with reservations.

It seems to us possible that the argon contained in living cells is of radioactive origin. It is known that the presence of potassium is necessary for any manifestation of life. It is known that this element (or at least one of its isotopes) is radioactive and emits β-rays. But we do not know what are its products of disintegration; it does not seem to us inadmissible that one of them is argon.

We are encouraged to make this hypothesis by the interesting observations recently published by M. Freundler and Mlles Ménager, Laurent and Lelièvre [Notes and Memoranda published by the Scientific and Technical Office of Maritime Fisheries, 41, 3 (1925); C. r. 180, 536 (1925)] on the equilibrium which exists in the tissues of marine algae between iodine and tin, a balance which could be explained, according to them, by a transformation of these elements into one another under the influence of life.

It is superfluous to insist on the importance that such research may acquire for the knowledge of biological phenomena; for our part, we will continue ours with all possible activity.

Geneva, Laboratory of Organic Chemistry of the University.

Sadly their work was never continued. This was for two reasons:

- Despite a mainstream acceptance of chemical isotope transmutations by means of natural radioactive decay, the suggestion of a “[transmutation of] elements into one another under the influence of life” was tantamount to an acceptance of vitalism, which mainstream science had rejected more seventy years previously. [This is discussed in more detail in chapter 9.]

- The radioactive decay of the potassium 40 isotope is complex, and was not fully understood until the 1950s or ’60s.

- Pictet and his colleagues were not nuclear chemists. To speculate about a phenomenon outside of their area of authority resulted in the dismissal of their work [for an example of such a dismissal see Memoir II: The Elementary Chemical Composition of Marine Organisms (2018) by A. P. Vinogradov].

… More biological transmutation experimental evidence to come, such as Freundler (Freundler, Menager et Laurent, 1925), the historical review of Biberian, Nuclear Science Abstracts, Volumes 1-3, Oak Ridge Directed Operations, Technical Information Division, 1949, and any other results I may find…

…

Leave a comment