The mysteries to be explored in this book largely fall under the subject matter of chemistry. Though I was not particularly talented at school or university in the practical art of chemistry, I have always been fascinated by its magical qualities. There is something deeply mysterious about it. I remember as a child seeing a painting of an alchemist’s laboratory and wishing that I might possess such a wondrous room. However, I have only never been able to attain more than the position of sorcerer’s apprentice, for the seemingly magical material transitions and transformations encountered in a chemist’s laboratory require an inner quality from the chemist which I myself have lacked. Though Rudolf Steiner was referring to the realm of the living when he said that ‘the laboratory workbench must first become an altar‘ [The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric, and elsewhere], it is a sentiment with which I wholeheartedly agree.

Nevertheless, the history of chemistry is effectively a story of the progressive loss of magic, systematically replaced by clear mathematical thinking. This is something which I recall reading Rudolf Steiner saying was a necessary thing. Part of my homework for this chapter is to find, read and understand just exactly what Steiner did say [I have been known to make mistakes!]…

This first chapter will probably be a more or less conventional historical review of the early developments of chemistry in the West. It is likely to cover much of the same ground as that of the first parts of the Wikipedia page: History of Chemistry, which I give (slightly edited) below:

Early humans

A 100,000-year-old ochre-processing workshop was found at Blombos Cave in South Africa. It indicates that early humans had an elementary knowledge of chemistry. Paintings drawn by early humans consisting of early humans mixing animal blood with other liquids found on cave walls also indicate a small knowledge of chemistry.[2][3]

Early metallurgy

Main articles: History of ferrous metallurgy and History of metallurgy in the Indian subcontinent

The earliest recorded metal employed by humans seems to be gold, which can be found free or “native”. Small amounts of natural gold have been found in Spanish caves used during the late Paleolithic period, around 40,000 BC.[4]

Silver, copper, tin and meteoric iron can also be found native, allowing a limited amount of metalworking in ancient cultures.[5] Egyptian weapons made from meteoric iron in about 3000 BC were highly prized as “daggers from Heaven”.[6]

Arguably the first chemical reaction used in a controlled manner was fire. However, for millennia fire was seen simply as a mystical force that could transform one substance into another (burning wood, or boiling water) while producing heat and light. Fire affected many aspects of early societies. These ranged from the simplest facets of everyday life, such as cooking and habitat heating and lighting, to more advanced uses, such as for making pottery and bricks and melting of metals to make tools.

It was fire that led to the discovery of glass and the purification of metals; this was followed by the rise of metallurgy.[7] During the early stages of metallurgy, methods of purification of metals were sought, and gold, known in ancient Egypt as early as 2900 BC, became a precious metal.

Bronze Age

Certain metals can be recovered from their ores by simply heating the rocks in a fire: notably tin, lead and (at a higher temperature) copper. This process is known as smelting. The first evidence of this extractive metallurgy dates from the 6th and 5th millennia BC, and was found in the archaeological sites of Majdanpek, Yarmovac and Plocnik, all three in Serbia. To date, the earliest copper smelting is found at the Belovode site;[8] these examples include a copper axe from 5500 BC belonging to the Vinča culture.[9] Other signs of early metals are found from the third millennium BC in places like Palmela (Portugal), Los Millares (Spain), and Stonehenge (United Kingdom). However, as often happens in the study of prehistoric times, the ultimate beginnings cannot be clearly defined and new discoveries are ongoing.

These first metals were single elements, or else combinations as naturally occurred. By combining copper and tin, a superior metal could be made, an alloy called bronze. This was a major technological shift which began the Bronze Age about 3500 BC. The Bronze Age was a period in human cultural development when the most advanced metalworking (at least in systematic and widespread use) included techniques for smelting copper and tin from naturally occurring outcroppings of copper ores, and then smelting those ores to cast bronze. These naturally occurring ores typically included arsenic as a common impurity. Copper/tin ores are rare, as reflected in the absence of tin bronzes in western Asia before 3000 BC.

Iron Age

The extraction of iron from its ore into a workable metal is much more difficult than copper or tin. While iron is not better suited for tools than bronze (until steel was discovered), iron ore is much more abundant and common than either copper or tin, and therefore more often available locally, with no need to trade for it.

Iron working appears to have been invented by the Hittites in about 1200 BC, beginning the Iron Age. The secret of extracting and working iron was a key factor in the success of the Philistines.[6][11]

The Iron Age refers to the advent of iron working (ferrous metallurgy). Historical developments in ferrous metallurgy can be found in a wide variety of past cultures and civilizations. These include the ancient and medieval kingdoms and empires of the Middle East and Near East, ancient Iran, ancient Egypt, ancient Nubia, and Anatolia (Turkey), Ancient Nok, Carthage, the Greeks and Romans of ancient Europe, medieval Europe, ancient and medieval China, ancient and medieval India, ancient and medieval Japan, amongst others. Many applications, practices, and devices associated with or involved in metallurgy were established in ancient China, such as the innovation of the blast furnace, cast iron, hydraulic-powered trip hammers, and double-acting piston bellows.[12][13]

Classical antiquity and atomism

Philosophical attempts to rationalize why different substances have different properties (colour, density, smell), exist in different states (gaseous, liquid, and solid), and react in a different manner when exposed to environments, for example to water or fire or temperature changes, led ancient philosophers to postulate the first theories on nature and chemistry. The history of such philosophical theories that relate to chemistry can probably be traced back to every single ancient civilization. The common aspect in all these theories was the attempt to identify a small number of primary classical elements that make up all the various substances in nature. Substances like air, water, and soil/earth, energy forms, such as fire and light, and more abstract concepts such as thoughts, aether, and heaven, were common in ancient civilizations even in the absence of any cross-fertilization: for example ancient Greek, Indian, Mayan, and Chinese philosophies all considered air, water, earth and fire as primary elements.

Ancient world

Around 420 BC, Empedocles stated that all matter is made up of four elemental substances: earth, fire, air and water. The early theory of atomism can be traced back to ancient Greece and ancient India.[14] Greek atomism dates back to the Greek philosopher Democritus, who declared that matter is composed of indivisible and indestructible particles called “atomos” around 380 BC. Leucippus also declared that atoms were the most indivisible part of matter. This coincided with a similar declaration by Indian philosopher Kanada in his Vaisheshika sutras around the same time period.[14] In much the same fashion he discussed the existence of gases. What Kanada declared by sutra, Democritus declared by philosophical musing. Both suffered from a lack of empirical data. Without scientific proof, the existence of atoms was easy to deny. Aristotle opposed the existence of atoms in 330 BC. Earlier, in 380 BC, a Greek text attributed to Polybus argued that the human body is composed of four humours. Around 300 BC, Epicurus postulated a universe of indestructible atoms in which man himself is responsible for achieving a balanced life.

With the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience, the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius[15] wrote De rerum natura (The Nature of Things)[16] in 50 BC. In the work, Lucretius presents the principles of atomism; the nature of the mind and soul; explanations of sensation and thought; the development of the world and its phenomena; and explains a variety of celestial and terrestrial phenomena.

Much of the early development of purification methods is described by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia. He tried to explain those methods, as well as making acute observations of the state of many minerals.

Medieval alchemy

See also: Minima naturalia, a medieval Aristotelian concept analogous to atomism

The elemental system used in medieval alchemy was developed primarily by the Persian–Arab alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān and was rooted in the classical elements of Greek tradition.[17] His system consisted of the four Aristotelian elements of air, earth, fire, and water in addition to two philosophical elements: sulphur, characterizing the principle of combustibility, “the stone which burns”; and mercury, characterizing the principle of metallic properties. They were seen by early alchemists as idealized expressions of irreducible components of the universe[18] and are of larger consideration[clarification needed] within philosophical alchemy.

The three metallic principles (sulphur to flammability or combustion, mercury to volatility and stability, and salt to solidity) became the tria prima of the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus. He reasoned that Aristotle’s four-element theory appeared in bodies as three principles. Paracelsus saw these principles as fundamental and justified them by recourse to the description of how wood burns in fire. Mercury included the cohesive principle, so that when it left the wood (in smoke) the wood fell apart. Smoke described the volatility (the mercurial principle), the heat-giving flames described flammability (sulphur), and the remnant ash described solidity (salt).[19]

The philosopher’s stone

Alchemy is defined by the Hermetic quest for the philosopher’s stone, the study of which is steeped in symbolic mysticism, and differs greatly from modern science. Alchemists toiled to make transformations on an esoteric (spiritual) and/or exoteric (practical) level.[20] It was the protoscientific, exoteric aspects of alchemy that contributed heavily to the evolution of chemistry in Greco-Roman Egypt, in the Islamic Golden Age, and then in Europe. Alchemy and chemistry share an interest in the composition and properties of matter, and until the 18th century they were not separate disciplines. The term chymistry has been used to describe the blend of alchemy and chemistry that existed before that time.[21]

The earliest Western alchemists, who lived in the first centuries of the common era, invented chemical apparatus. The bain-marie, or water bath, is named for Mary the Jewess. Her work also gives the first descriptions of the tribikos and kerotakis.[22] Cleopatra the Alchemist described furnaces and has been credited with the invention of the alembic.[23] Later, the experimental framework established by Jabir ibn Hayyan influenced alchemists as the discipline migrated through the Islamic world, then to Europe in the 12th century CE.

During the Renaissance, exoteric alchemy remained popular in the form of Paracelsian iatrochemistry, while spiritual alchemy flourished, realigned to its Platonic, Hermetic, and Gnostic roots. Consequently, the symbolic quest for the philosopher’s stone was not superseded by scientific advances, and was still the domain of respected scientists and doctors until the early 18th century. Early modern alchemists who are renowned for their scientific contributions include Jan Baptist van Helmont, Robert Boyle, and Isaac Newton.

Alchemy in the Islamic world

In the Islamic World, the Muslims were translating the works of the ancient Greeks and Egyptians into Arabic and were experimenting with scientific ideas.[24] The development of the modern scientific method was slow and arduous, but an early scientific method for chemistry began emerging among early Muslim chemists, beginning with the 9th-century chemist Jābir ibn Hayyān (known as “Geber” in Europe), who is sometimes regarded as “the father of chemistry”.[25][26][27][28] He introduced a systematic and experimental approach to scientific research based in the laboratory, in contrast to the ancient Greek and Egyptian alchemists whose works were largely allegorical and often unintelligible.[29] He also invented and named the alembic (al-anbiq), chemically analyzed many chemical substances, composed lapidaries, distinguished between alkalis and acids, and manufactured hundreds of drugs.[30] He also refined the theory of five classical elements into the theory of seven alchemical elements after identifying mercury and sulfur as chemical elements.[31][verification needed]

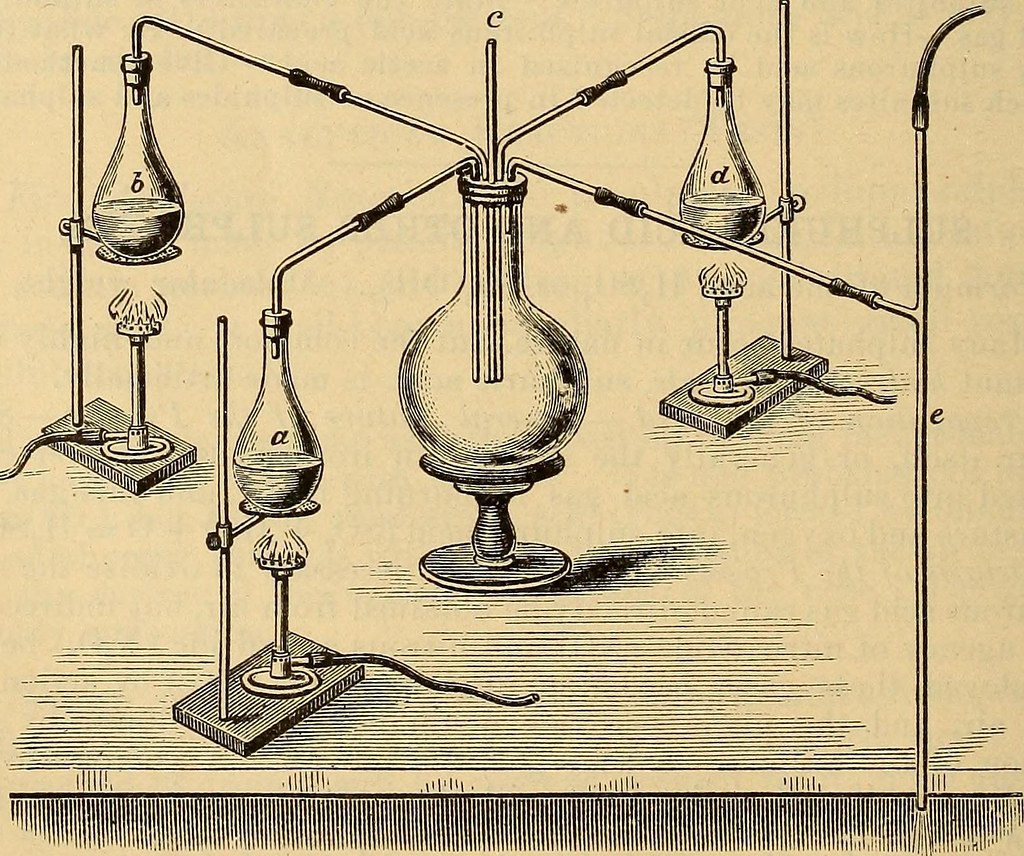

Among other influential Muslim chemists, Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī,[32] Avicenna[33] and Al-Kindi refuted the theories of alchemy, particularly the theory of the transmutation of metals; and al-Tusi described a version of the conservation of mass, noting that a body of matter is able to change but is not able to disappear.[34] Rhazes refuted Aristotle‘s theory of four classical elements for the first time and set up the firm foundations of modern chemistry, using the laboratory in the modern sense, designing and describing more than twenty instruments, many parts of which are still in use today, such as a crucible, cucurbit or retort for distillation, and the head of a still with a delivery tube (ambiq, Latin alembic), and various types of furnace or stove.[citation needed]

Problems encountered with alchemy

There were several problems with alchemy, as seen from today’s standpoint. There was no systematic naming scheme for new compounds, and the language was esoteric and vague to the point that the terminologies meant different things to different people. In fact, according to The Fontana History of Chemistry (Brock, 1992):

The language of alchemy soon developed an arcane and secretive technical vocabulary designed to conceal information from the uninitiated. To a large degree, this language is incomprehensible to us today, though it is apparent that readers of Geoffery Chaucer‘s Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale or audiences of Ben Jonson‘s The Alchemist were able to construe it sufficiently to laugh at it.[35]

Chaucer’s tale exposed the more fraudulent side of alchemy, especially the manufacture of counterfeit gold from cheap substances. Less than a century earlier, Dante Alighieri also demonstrated an awareness of this fraudulence, causing him to consign all alchemists to the Inferno in his writings. Soon afterwards, in 1317, the Avignon Pope John XXII ordered all alchemists to leave France for making counterfeit money. A law was passed in England in 1403 which made the “multiplication of metals” punishable by death. Despite these and other apparently extreme measures, alchemy did not die. Royalty and privileged classes still sought to discover the philosopher’s stone and the elixir of life for themselves.[36]

There was also no agreed-upon scientific method for making experiments reproducible. Indeed, many alchemists included in their methods irrelevant information such as the timing of the tides or the phases of the moon[??!]. The esoteric nature and codified vocabulary of alchemy appeared to be more useful in concealing the fact that they could not be sure of very much at all[?!]. As early as the 14th century, cracks seemed to grow in the facade of alchemy; and people became sceptical.[citation needed] Clearly, there needed to be a scientific method in which experiments could be repeated by other people, and results needed to be reported in a clear language that laid out both what was known and what was unknown.

17th and 18th centuries: Early chemistry

Practical attempts to improve the refining of ores and their extraction to smelt metals was an important source of information for early chemists in the 16th century, among them Georg Agricola (1494–1555), who published his great work De re metallica in 1556. His work describes the highly developed and complex processes of mining metal ores, metal extraction and metallurgy of the time. His approach removed the mysticism associated with the subject, creating the practical base upon which others could build. The work describes the many kinds of furnace used to smelt ore, and stimulated interest in minerals and their composition. It is no coincidence that he gives numerous references to the earlier author, Pliny the Elder and his Naturalis Historia. Agricola has been described as the “father of metallurgy”.[37]

In 1605, Sir Francis Bacon published The Proficience and Advancement of Learning, which contains a description of what would later be known as the scientific method.[38] In 1605, Michal Sedziwój published the alchemical treatise A New Light of Alchemy which proposed the existence of the “food of life” within air, much later recognized as oxygen. In 1615 Jean Beguin published the Tyrocinium Chymicum, an early chemistry textbook, and in it draws the first-ever chemical equation.[39] In 1637 René Descartes publishes Discours de la méthode, which contains an outline of the scientific method.

The Dutch chemist Jan Baptist van Helmont‘s work Ortus medicinae was published posthumously in 1648; the book is cited by some as a major transitional work between alchemy and chemistry, and as an important influence on Robert Boyle. The book contains the results of numerous experiments and establishes an early version of the law of conservation of mass. Working during the time just after Paracelsus and iatrochemistry, Jan Baptist van Helmont suggested that there are insubstantial substances other than air and coined a name for them – “gas“, from the Greek word chaos. In addition to introducing the word “gas” into the vocabulary of scientists, van Helmont conducted several experiments involving gases. Jan Baptist van Helmont is also remembered today largely for his ideas on spontaneous generation and his 5-year tree experiment, as well as being considered the founder of pneumatic chemistry.

Robert Boyle

Anglo-Irish chemist Robert Boyle (1627–1691) is considered to have refined the modern scientific method for alchemy and to have separated chemistry further from alchemy.[40] Although his research clearly has its roots in the alchemical tradition, Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of modern chemistry, and one of the pioneers of modern experimental scientific method. Although Boyle was not the original discoverer, he is best known for Boyle’s law, which he presented in 1662:[41] the law describes the inversely proportional relationship between the absolute pressure and volume of a gas, if the temperature is kept constant within a closed system.[42][43]

Boyle is also credited for his landmark publication The Sceptical Chymist in 1661, which is seen as a cornerstone book in the field of chemistry. In the work, Boyle presents his hypothesis that every phenomenon was the result of collisions of particles in motion. Boyle appealed to chemists to experiment and asserted that experiments denied the limiting of chemical elements to only the classic four: earth, fire, air, and water. He also pleaded that chemistry should cease to be subservient to medicine or to alchemy, and rise to the status of a science. Importantly, he advocated a rigorous approach to scientific experiment: he believed all theories must be proved experimentally before being regarded as true. The work contains some of the earliest modern ideas of atoms, molecules, and chemical reaction, and marks the beginning of the history of modern chemistry.

Boyle also tried to purify chemicals to obtain reproducible reactions. He was a vocal proponent of the mechanical philosophy proposed by René Descartes to explain and quantify the physical properties and interactions of material substances. Boyle was an atomist, but favoured the word corpuscle over atoms. He commented that the finest division of matter where the properties are retained is at the level of corpuscles. He also performed numerous investigations with an air pump, and noted that the mercury fell as air was pumped out. He also observed that pumping the air out of a container would extinguish a flame and kill small animals placed inside. Boyle helped to lay the foundations for the Chemical Revolution with his mechanical corpuscular philosophy.[44] Boyle repeated the tree experiment of van Helmont, and was the first to use indicators which changed colors with acidity.

Development and dismantling of phlogiston

In 1702, German chemist Georg Stahl coined the name “phlogiston” for the substance believed to be released in the process of burning. Around 1735, Swedish chemist Georg Brandt analyzed a dark blue pigment found in copper ore. Brandt demonstrated that the pigment contained a new element, later named cobalt. In 1751, a Swedish chemist and pupil of Stahl’s named Axel Fredrik Cronstedt, identified an impurity in copper ore as a separate metallic element, which he named nickel. Cronstedt is one of the founders of modern mineralogy.[45] Cronstedt also discovered the mineral scheelite in 1751, which he named tungsten, meaning “heavy stone” in Swedish.

In 1754, Scottish chemist Joseph Black isolated carbon dioxide, which he called “fixed air”.[46] In 1757, Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt, while investigating arsenic compounds, created Cadet’s fuming liquid, later discovered to be cacodyl oxide, considered to be the first synthetic organometallic compound.[47] In 1758, Joseph Black formulated the concept of latent heat to explain the thermochemistry of phase changes.[48] In 1766, English chemist Henry Cavendish isolated hydrogen, which he called “inflammable air”. Cavendish discovered hydrogen as a colorless, odourless gas that burns and can form an explosive mixture with air, and published a paper on the production of water by burning inflammable air (that is, hydrogen) in dephlogisticated air (now known to be oxygen), the latter a constituent of atmospheric air (phlogiston theory).

In 1773, Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele discovered oxygen, which he called “fire air”, but did not immediately publish his achievement.[49] In 1774, English chemist Joseph Priestley independently isolated oxygen in its gaseous state, calling it “dephlogisticated air”, and published his work before Scheele.[50][51] During his lifetime, Priestley’s considerable scientific reputation rested on his invention of soda water, his writings on electricity, and his discovery of several “airs” (gases), the most famous being what Priestley dubbed “dephlogisticated air” (oxygen). However, Priestley’s determination to defend phlogiston theory and to reject what would become the chemical revolution eventually left him isolated within the scientific community.

In 1781, Carl Wilhelm Scheele discovered that a new acid, tungstic acid, could be made from Cronstedt’s scheelite (at the time named tungsten). Scheele and Torbern Bergman suggested that it might be possible to obtain a new metal by reducing this acid.[52] In 1783, José and Fausto Elhuyar found an acid made from wolframite that was identical to tungstic acid. Later that year, in Spain, the brothers succeeded in isolating the metal now known as tungsten by reduction of this acid with charcoal, and they are credited with the discovery of the element.[53][54]

Volta and the Voltaic pile

Italian physicist Alessandro Volta constructed a device for accumulating a large charge by a series of inductions and groundings. He investigated the 1780s discovery “animal electricity” by Luigi Galvani, and found that the electric current was generated from the contact of dissimilar metals, and that the frog leg was only acting as a detector. Volta demonstrated in 1794 that when two metals and brine-soaked cloth or cardboard are arranged in a circuit they produce an electric current.

In 1800, Volta stacked several pairs of alternating copper (or silver) and zinc discs (electrodes) separated by cloth or cardboard soaked in brine (electrolyte) to increase the electrolyte conductivity.[55] When the top and bottom contacts were connected by a wire, an electric current flowed through the voltaic pile and the connecting wire. Thus, Volta is credited with constructing the first electrical battery to produce electricity. Volta’s method of stacking round plates of copper and zinc separated by disks of cardboard moistened with salt solution was termed a voltaic pile.

Thus, Volta is considered to be the founder of the discipline of electrochemistry.[56] A Galvanic cell (or voltaic cell) is an electrochemical cell that derives electrical energy from spontaneous redox reaction taking place within the cell. It generally consists of two different metals connected by a salt bridge, or individual half-cells separated by a porous membrane.

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier

Main articles: Antoine Lavoisier and Chemical Revolution

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier demonstrated with careful measurements that transmutation of water to earth was not possible, but that the sediment observed from boiling water came from the container. He burnt phosphorus and sulfur in air, and proved that the products weighed more than the original. Nevertheless, the weight gained was lost from the air. Thus, in 1789, he established the Law of Conservation of Mass, which is also called “Lavoisier’s Law.”[57]The world’s first ice-calorimeter, used in the winter of 1782–83, by Antoine Lavoisier and Pierre-Simon Laplace, to determine the heat involved in various chemical changes; calculations which were based on Joseph Black’s prior discovery of latent heat. These experiments mark the foundation of thermochemistry.

Repeating the experiments of Priestley, he demonstrated that air is composed of two parts, one of which combines with metals to form calxes. In Considérations Générales sur la Nature des Acides (1778), he demonstrated that the “air” responsible for combustion was also the source of acidity. The next year, he named this portion oxygen (Greek for acid-former), and the other azote (Greek for no life). Lavoisier thus has a claim to the discovery of oxygen along with Priestley and Scheele. He also discovered that the “inflammable air” discovered by Cavendish – which he termed hydrogen (Greek for water-former) – combined with oxygen to produce a dew, as Priestley had reported, which appeared to be water. In Reflexions sur le Phlogistique (1783), Lavoisier showed the phlogiston theory of combustion to be inconsistent. Mikhail Lomonosov independently established a tradition of chemistry in Russia in the 18th century. Lomonosov also rejected the phlogiston theory, and anticipated the kinetic theory of gases. Lomonosov regarded heat as a form of motion, and stated the idea of conservation of matter.

Lavoisier worked with Claude Louis Berthollet and others to devise a system of chemical nomenclature which serves as the basis of the modern system of naming chemical compounds. In his Methods of Chemical Nomenclature (1787), Lavoisier invented the system of naming and classification still largely in use today, including names such as sulfuric acid, sulfates, and sulfites. In 1785, Berthollet was the first to introduce the use of chlorine gas as a commercial bleach. In the same year he first determined the elemental composition of the gas ammonia. Berthollet first produced a modern bleaching liquid in 1789 by passing chlorine gas through a solution of sodium carbonate – the result was a weak solution of sodium hypochlorite. Another strong chlorine oxidant and bleach which he investigated and was the first to produce, potassium chlorate (KClO3), is known as Berthollet’s Salt. Berthollet is also known for his scientific contributions to theory of chemical equilibria via the mechanism of reverse chemical reactions.

Lavoisier’s Traité Élémentaire de Chimie (Elementary Treatise of Chemistry, 1789) was the first modern chemical textbook, and presented a unified view of new theories of chemistry, contained a clear statement of the Law of Conservation of Mass, and denied the existence of phlogiston. In addition, it contained a list of elements, or substances that could not be broken down further, which included oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, phosphorus, mercury, zinc, and sulfur. His list, however, also included light, and caloric, which he believed to be material substances. In the work, Lavoisier underscored the observational basis of his chemistry, stating “I have tried…to arrive at the truth by linking up facts; to suppress as much as possible the use of reasoning, which is often an unreliable instrument which deceives us, in order to follow as much as possible the torch of observation and of experiment.” Nevertheless, he believed that the real existence of atoms was philosophically impossible. Lavoisier demonstrated that organisms disassemble and reconstitute atmospheric air in the same manner as a burning body.

With Pierre-Simon Laplace, Lavoisier used a calorimeter to estimate the heat evolved per unit of carbon dioxide produced. They found the same ratio for a flame and animals, indicating that animals produced energy by a type of combustion. Lavoisier believed in the radical theory, believing that radicals, which function as a single group in a chemical reaction, would combine with oxygen in reactions. He believed all acids contained oxygen. He also discovered that diamond is a crystalline form of carbon.

While many of Lavoisier’s partners were influential for the advancement of chemistry as a scientific discipline, his wife Marie-Anne Lavoisier was arguably the most influential of them all. Upon their marriage, Mme. Lavoisier began to study chemistry, English, and drawing in order to help her husband in his work either by translating papers into English, a language which Lavoisier did not know, or by keeping records and drawing the various apparatuses that Lavoisier used in his labs.[58] Through her ability to read and translate articles from Britain for her husband, Lavoisier had access knowledge from many of the chemical advances happening outside of his lab.[58] Furthermore, Mme. Lavoisier kept records of Lavoisier’s work and ensured that his works were published.[58] The first sign of Marie-Anne’s true potential as a chemist in Lavoisier’s lab came when she was translating a book by the scientist Richard Kirwan. While translating, she stumbled upon and corrected multiple errors. When she presented her translation, along with her notes to Lavoisier [58] Her edits and contributions led to Lavoisier’s refutation of the theory of phlogiston.

Lavoisier made many fundamental contributions to the science of chemistry. Following Lavoisier’s work, chemistry acquired a strict quantitative nature, allowing reliable predictions to be made. The revolution in chemistry which he brought about was a result of a conscious effort to fit all experiments into the framework of a single theory. He established the consistent use of chemical balance, used oxygen to overthrow the phlogiston theory, and developed a new system of chemical nomenclature. Lavoisier was beheaded during the French Revolution.

One of the main reasons for ending the chapter with Lavoisier was his conservation law. It is this law, and its exceptions, which form one of the golden threads of this work.

Leave a comment